What follows is a selection of articles - the equivalent of a 'tasting menu'.

They are in no particular order or chronology - so, if you don't like starting with the dessert, skip to the next course…

Bonne Dégustation!

* and please note: they are all copyright - mine, the publisher's, or both

They are in no particular order or chronology - so, if you don't like starting with the dessert, skip to the next course…

Bonne Dégustation!

* and please note: they are all copyright - mine, the publisher's, or both

For starters, here are three articles about living in France - both as a second-home owner and as a permanent resident. We - my wife and I - have experienced both and the articles follow our thirty-year relationship with the country : from the UK to France... to Australia... back to France... and, in early 2020, back to Australia where we are now again resident.

THE FINANCIAL TIMES

20/21 SEPTEMBER 1997

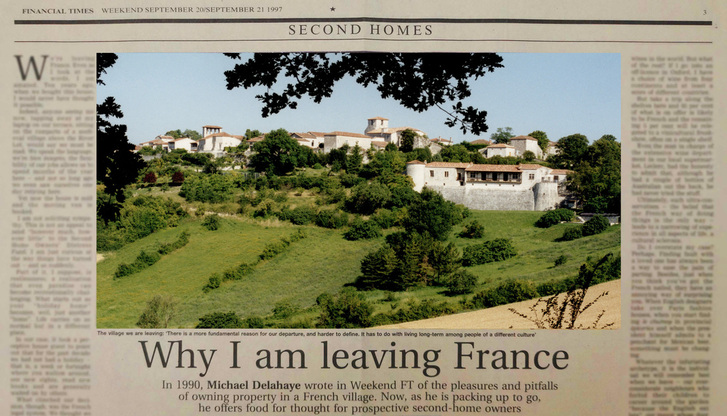

Photo: MD

In 1990, Michael Delahaye wrote in Weekend FT of the pleasures and pitfalls of owning property in a French village. Now, as he is packing up to go, he offers food for thought for prospective second-home owners

We're leaving France. Even as I look at the words, I am amazed. Ten years ago, when we bought this house, I would never have thought it possible. Indeed, anyone seeing me now, tapping away at my laptop on our terrace, sitting on the ramparts of a medieval village above the River Lot, would say we must be mad. We speak the language, we're bien intégrés, the flexibility of our jobs allows us to spend months of the year here - and not so long ago we even saw ourselves one day retiring here. Yet now the house is sold and the moving van is booked. I am not soliciting sympathy. This is not an appeal to send 'however much, however little' to the Second Home Owners' Distress Fund. I am just curious at the way things have turned out - and so suddenly.

Part of it, I suppose, is restlessness: a realisation that even paradise can become recreationally challenging. What starts out as your 'holiday home' becomes, well, just another 'home'. Life carries on as normal but in a different place. In our case, it took a perceptive house guest to point out that for the past decade we had not had a holiday - that is, a week or fortnight where you wallow around, see new sights, read new books and are generally waited on by others.

What clinched our decision, though, was the French legal system. We thought we had covered everything - until, belatedly, we came to make a French will and encountered La Loi de Succession. It was then we discovered that, because I had never formally adopted my step-daughter, she would have to pay 60% of the house's market value in taxes if she were to inherit it directly from me. There are some elaborate ways round it but none applicable to our circumstances. Perhaps we should not have been surprised. I have before me our latest electricity bill. It's for FFr 1,600. But 44% of that - FFr 700 - is made up of the standing charge, VAT and local taxes. Looking more closely, I see VAT has even been levied on the local taxes.

But yes, I hear what you say: if one chooses to live in someone else's country, one should be prepared to pay the price. And we probably would - if the village itself had not started to change. When we arrived, it had a pleasantly neglected air - the world forgetting and by the world forgot. But those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first put on the tourist map. Three years ago the village was elevated to the ranks of Les Plus Beaux Villages de France. Since then it has been so gentrified - embourgeoisé - that you can no longer turn a corner without tripping over a geranium. For a time we even had a full-scale working guillotine outside our front gate, as 'a historical aid for foreigners'.

But there is a more fundamental reason for our departure, and harder to define. It has to do with living long-term among people of a different culture. Since half my family comes from the Channel island of Jersey, I hardly qualify as a Little Englander. In fact, my grandmother spoke a local patois that the English could not distinguish from French (nor the French from gibberish).

No, I like the French. I like the essential civility of the people, the way they greet each other, the hand-shaking and double-kissing, the way they are not afraid to touch. I like the way their children learn from the moment they walk to 'present' themselves, not to remain glued to the telly when adult visitors enter the room. I like the French attitude to alcohol - as something to be drunk, not to make you drunk. And I like the way our town hall can turn even the biannual distribution of the household rubbish bags into an occasion that would not disgrace the Elysée Palace.

But here's the strange thing. While in any French street or square you will find this politesse at every turn, as soon as you climb into a car, it evaporates. No wonder that, in spite of having the same size population as the UK, they kill twice as many of their fellow countrymen on their roads. The exception, incidentally, is cycling. I can vouch that French drivers have an almost reverential respect for anything on two wheels.

Which brings me to the wider point. For its combination of climate, countryside, culture and cuisine, France has no equal. But it is not perfect.

Yet try, as a foreigner, suggesting to a Frenchman that perhaps not every restaurant in France is of the first order, that indeed it is surprisingly easy to eat badly here - and you will be reminded that the English have no taste. The argument is not so much that, being English, you cannot judge the matter but that, not being French, you will always lack the necessary discernment.

Take wine as an example. I am no expert but I am prepared to believe that the best French wines are the best wines in the world. But what of the rest? If I go into an off-licence in Oxford, I have a choice of wine from four continents and at least a score of different countries. But take a trip along the shelves here and 95% of what is on offer is likely to be French and the remaining 5% will be relegated to a vinicultural freak show, often on a single shelf. Even the man in charge of the extensive wine department in our local supermarket, Leclerc, had the honesty to admit that, although he had a couple of Australian out the back, he had never tried the stuff. Ultimately, such ultra-conservatism - the belief that the French way of doing things is the only way - leads to a narrowing of experience in all aspects of life, a cultural sclerosis.

Do I overstate my case? Perhaps. Finding fault with a loved one has always been a way to ease the pain of parting. Besides, just when you think you've got the French nailed, they have an annoying way of surprising you. When English designers take over Paris fashion houses, when you start finding le chutney in provincial épiceries and when the President himself admits to a penchant for Mexican beer, something must be changing. Whatever the infuriating archetype, it is the individual we will remember best when we leave - our ever-considerate neighbours who forbid their children to career around the garden 'because the English eat late', our mayor whose door has always been open to us, and our postman who, when asked what sort of day he thinks it's going to be, can be relied on to reply: 'How should I know? I'm a postman, not a meteorologist!'.

Even so, I fear it would have been some time before we would have persuaded our local restaurateur that the cheese that goes into a genuine mozzarella and tomato salad is the sort sliced from a ball, not industrial-grade granules used to retread pizzas. Better perhaps to leave it to an Italian to enlighten him. It was after all Henri II's queen, Catherine de' Medici, who first taught the French how to cook. But don't tell them that.

POSTSCRIPT: This article came back to bite me fifteen years later when in the summer of 2013 we bought again in France - a very modest pied-à-terre in the Dordogne - before moving permanently in early 2016. By way of eating humble pie, I wrote a second article - this time for THE CONNEXION, France's most widely circulated English-language newspaper. See next...

20/21 SEPTEMBER 1997

Photo: MD

In 1990, Michael Delahaye wrote in Weekend FT of the pleasures and pitfalls of owning property in a French village. Now, as he is packing up to go, he offers food for thought for prospective second-home owners

We're leaving France. Even as I look at the words, I am amazed. Ten years ago, when we bought this house, I would never have thought it possible. Indeed, anyone seeing me now, tapping away at my laptop on our terrace, sitting on the ramparts of a medieval village above the River Lot, would say we must be mad. We speak the language, we're bien intégrés, the flexibility of our jobs allows us to spend months of the year here - and not so long ago we even saw ourselves one day retiring here. Yet now the house is sold and the moving van is booked. I am not soliciting sympathy. This is not an appeal to send 'however much, however little' to the Second Home Owners' Distress Fund. I am just curious at the way things have turned out - and so suddenly.

Part of it, I suppose, is restlessness: a realisation that even paradise can become recreationally challenging. What starts out as your 'holiday home' becomes, well, just another 'home'. Life carries on as normal but in a different place. In our case, it took a perceptive house guest to point out that for the past decade we had not had a holiday - that is, a week or fortnight where you wallow around, see new sights, read new books and are generally waited on by others.

What clinched our decision, though, was the French legal system. We thought we had covered everything - until, belatedly, we came to make a French will and encountered La Loi de Succession. It was then we discovered that, because I had never formally adopted my step-daughter, she would have to pay 60% of the house's market value in taxes if she were to inherit it directly from me. There are some elaborate ways round it but none applicable to our circumstances. Perhaps we should not have been surprised. I have before me our latest electricity bill. It's for FFr 1,600. But 44% of that - FFr 700 - is made up of the standing charge, VAT and local taxes. Looking more closely, I see VAT has even been levied on the local taxes.

But yes, I hear what you say: if one chooses to live in someone else's country, one should be prepared to pay the price. And we probably would - if the village itself had not started to change. When we arrived, it had a pleasantly neglected air - the world forgetting and by the world forgot. But those whom the gods wish to destroy, they first put on the tourist map. Three years ago the village was elevated to the ranks of Les Plus Beaux Villages de France. Since then it has been so gentrified - embourgeoisé - that you can no longer turn a corner without tripping over a geranium. For a time we even had a full-scale working guillotine outside our front gate, as 'a historical aid for foreigners'.

But there is a more fundamental reason for our departure, and harder to define. It has to do with living long-term among people of a different culture. Since half my family comes from the Channel island of Jersey, I hardly qualify as a Little Englander. In fact, my grandmother spoke a local patois that the English could not distinguish from French (nor the French from gibberish).

No, I like the French. I like the essential civility of the people, the way they greet each other, the hand-shaking and double-kissing, the way they are not afraid to touch. I like the way their children learn from the moment they walk to 'present' themselves, not to remain glued to the telly when adult visitors enter the room. I like the French attitude to alcohol - as something to be drunk, not to make you drunk. And I like the way our town hall can turn even the biannual distribution of the household rubbish bags into an occasion that would not disgrace the Elysée Palace.

But here's the strange thing. While in any French street or square you will find this politesse at every turn, as soon as you climb into a car, it evaporates. No wonder that, in spite of having the same size population as the UK, they kill twice as many of their fellow countrymen on their roads. The exception, incidentally, is cycling. I can vouch that French drivers have an almost reverential respect for anything on two wheels.

Which brings me to the wider point. For its combination of climate, countryside, culture and cuisine, France has no equal. But it is not perfect.

Yet try, as a foreigner, suggesting to a Frenchman that perhaps not every restaurant in France is of the first order, that indeed it is surprisingly easy to eat badly here - and you will be reminded that the English have no taste. The argument is not so much that, being English, you cannot judge the matter but that, not being French, you will always lack the necessary discernment.

Take wine as an example. I am no expert but I am prepared to believe that the best French wines are the best wines in the world. But what of the rest? If I go into an off-licence in Oxford, I have a choice of wine from four continents and at least a score of different countries. But take a trip along the shelves here and 95% of what is on offer is likely to be French and the remaining 5% will be relegated to a vinicultural freak show, often on a single shelf. Even the man in charge of the extensive wine department in our local supermarket, Leclerc, had the honesty to admit that, although he had a couple of Australian out the back, he had never tried the stuff. Ultimately, such ultra-conservatism - the belief that the French way of doing things is the only way - leads to a narrowing of experience in all aspects of life, a cultural sclerosis.

Do I overstate my case? Perhaps. Finding fault with a loved one has always been a way to ease the pain of parting. Besides, just when you think you've got the French nailed, they have an annoying way of surprising you. When English designers take over Paris fashion houses, when you start finding le chutney in provincial épiceries and when the President himself admits to a penchant for Mexican beer, something must be changing. Whatever the infuriating archetype, it is the individual we will remember best when we leave - our ever-considerate neighbours who forbid their children to career around the garden 'because the English eat late', our mayor whose door has always been open to us, and our postman who, when asked what sort of day he thinks it's going to be, can be relied on to reply: 'How should I know? I'm a postman, not a meteorologist!'.

Even so, I fear it would have been some time before we would have persuaded our local restaurateur that the cheese that goes into a genuine mozzarella and tomato salad is the sort sliced from a ball, not industrial-grade granules used to retread pizzas. Better perhaps to leave it to an Italian to enlighten him. It was after all Henri II's queen, Catherine de' Medici, who first taught the French how to cook. But don't tell them that.

POSTSCRIPT: This article came back to bite me fifteen years later when in the summer of 2013 we bought again in France - a very modest pied-à-terre in the Dordogne - before moving permanently in early 2016. By way of eating humble pie, I wrote a second article - this time for THE CONNEXION, France's most widely circulated English-language newspaper. See next...

THE CONNEXION

NOVEMBER, 2015.

In 1997 Michael and Anni Delahaye sold their house in Aquitaine, disillusioned with France and the French, and emigrated to Australia. Eighteen years later, they are back… in France. Did they change or did the country?

Our story begins in Oxford during the particularly wet English summer of 1987. The date is August 4th. We have planned a barbecue and chosen the day deliberately. Surely it won’t dare to rain on the Queen Mother’s birthday? It doesn’t. It pours.

NOVEMBER, 2015.

In 1997 Michael and Anni Delahaye sold their house in Aquitaine, disillusioned with France and the French, and emigrated to Australia. Eighteen years later, they are back… in France. Did they change or did the country?

Our story begins in Oxford during the particularly wet English summer of 1987. The date is August 4th. We have planned a barbecue and chosen the day deliberately. Surely it won’t dare to rain on the Queen Mother’s birthday? It doesn’t. It pours.

That was the turning point. Within a few months, we’d bought a holiday home in France, far enough south to be assured of reasonable – and predictable – summer weather. And so for a decade we drove three times a year to and fro between Oxford and a stunning hilltop village in the Lot-et-Garonne. Our house was perched on the very edge of the village, its terrace comprising twenty metres of the medieval ramparts. In the evenings we would sit out with a glass of wine and listen to the nightingales and frogs below. As one guest put it, ‘If heaven isn’t as good as this, I’m not going’. Our teenage daughter spent her formative summers there and, in the last couple of years, my wife Anni set up a business making chutney for local restaurants and épiceries.

Then, bit by bit, the gilt started flaking off the gingerbread. The village changed. Fatally, it was elevated to the ranks of Les Plus Beaux Villages de France. The art galleries and regional produce shops moved in; the locals moved out. One morning we woke to find we had become extras in a medieval theme park.

We fell out not just with the place but with the people. Not so much the individuals as with the national conviction that the French way of doing everything was the best way, indeed the only way – whether cooking, wine, cinema, literature… you name it. The phrase that came to mind was ‘cultural sclerosis’. The last straw was the conversion into a restaurant of the barn opposite our house. The frogs and nightingales had to compete with music and revelry.

Just before we left in the autumn of 1997 I wrote a full-page article for the Financial Times, listing – exhaustively - our reasons for selling up. You could smell the burning boats.

In 2009 we sold our house in Oxford and left Europe altogether – for Australia, where Anni had grown up and still had family. Having a job that requires me only to be close to an airport, I was ready to experience a new life ‘down-under’. There was just one inconvenient fact… By this time, our daughter had married and had two children – our grandchildren. And they were all in Bath, Somerset. Ten thousand miles away.

So began an inter-continental migration for three months of the year back to the UK. While there, we would take in the rest of Europe - usually Italy but France too, even if only driving through. Time and again, like lovelorn adolescents, we found ourselves drawn to our old haunts. As we crossed into the Lot-et-Garonne, inane grins would creep across our faces. The shimmering poplars, the quaint pigeonniers, even the clichéd sunflowers… Emotionally if not physically, we were back.

We even revisited our old village – to discover that the subsequent owners of our house had stuck a monstrous carbuncle of a garage on the front and replaced the aged flagstones on the terrace with bathroom-grade commercial tiles. It hurt.

Coincidentally, a relative-in-law had meanwhile built a house in the area and generously made it available to us at a family rate. While staying there, we started glancing in estate agents windows… and even, very occasionally, we would view a property. Purely out of curiosity, you understand. By now there was also a financial consideration. After three years of living like executive gypsies in rented apartments and houses, we were shocked to realise that our European sojourns were costing us about £1000 a month – in addition to the unavoidable expenses back in Australia. There had to be a better way. A modest pied-à-terre perhaps?

Understandably, our daughter wanted us close to her and the family, in or around Bath. Our son-in-law tried to interest us in Jane Austen’s former basement but the appeal of reading ‘Pride and Prejudice’ in authentic period gloom was limited and brief. The other possibility was somewhere outside the UK but within reasonable flying time of nearby Bristol Airport… somewhere close to, say, Bergerac Airport.

In May 2012 we found ourselves in Monpazier, that most perfect of bastides in the Dordogne, just over the border from the Lot-et-Garonne. We called in on Annette, an estate agent we knew.

‘I’ve something that might interest you…’, she said. Ominous words.

The building of which the house formed the middle section had once been a hotel – some say a brothel – before being converted into separate units. The exterior was uninviting; anonymity had evidently been a requirement of the building’s alleged former function. The interior, though, was a revelation… The developer had punched out walls, changed levels and made the twisting 250-year old central staircase an open-plan feature of both the ground- and first- floors. But the biggest surprise, tucked away at the back, was a walled courtyard – a sought-after rarity in the heart of a medieval village.

Cursing our good fortune, we made an offer… then another… until finally the deal was done. It cost half Miss Austen’s dark, damp basement.

So who has changed – us or the French?

Both I suspect. We’ve come to appreciate what we had… lost… and missed. But the French too seem to have mellowed. Whether it’s the high unemployment, the divisive immigration debate or the sight of their young people seeking success across the Channel… the sharp edges have been rubbed off the old Gallic certainties of the Mitterrand and Chirac years. There seems to be more self-questioning. Even self-doubt.

With the occasional heart-warming exception… One morning, sipping coffee in our arcaded square in Monpazier, I listen in disbelief as another resident, an ex-Parisian, remarks that France is the only country in the world which she can imagine devoting a television programme to books and reading.

It’s good to be back.

Then, bit by bit, the gilt started flaking off the gingerbread. The village changed. Fatally, it was elevated to the ranks of Les Plus Beaux Villages de France. The art galleries and regional produce shops moved in; the locals moved out. One morning we woke to find we had become extras in a medieval theme park.

We fell out not just with the place but with the people. Not so much the individuals as with the national conviction that the French way of doing everything was the best way, indeed the only way – whether cooking, wine, cinema, literature… you name it. The phrase that came to mind was ‘cultural sclerosis’. The last straw was the conversion into a restaurant of the barn opposite our house. The frogs and nightingales had to compete with music and revelry.

Just before we left in the autumn of 1997 I wrote a full-page article for the Financial Times, listing – exhaustively - our reasons for selling up. You could smell the burning boats.

In 2009 we sold our house in Oxford and left Europe altogether – for Australia, where Anni had grown up and still had family. Having a job that requires me only to be close to an airport, I was ready to experience a new life ‘down-under’. There was just one inconvenient fact… By this time, our daughter had married and had two children – our grandchildren. And they were all in Bath, Somerset. Ten thousand miles away.

So began an inter-continental migration for three months of the year back to the UK. While there, we would take in the rest of Europe - usually Italy but France too, even if only driving through. Time and again, like lovelorn adolescents, we found ourselves drawn to our old haunts. As we crossed into the Lot-et-Garonne, inane grins would creep across our faces. The shimmering poplars, the quaint pigeonniers, even the clichéd sunflowers… Emotionally if not physically, we were back.

We even revisited our old village – to discover that the subsequent owners of our house had stuck a monstrous carbuncle of a garage on the front and replaced the aged flagstones on the terrace with bathroom-grade commercial tiles. It hurt.

Coincidentally, a relative-in-law had meanwhile built a house in the area and generously made it available to us at a family rate. While staying there, we started glancing in estate agents windows… and even, very occasionally, we would view a property. Purely out of curiosity, you understand. By now there was also a financial consideration. After three years of living like executive gypsies in rented apartments and houses, we were shocked to realise that our European sojourns were costing us about £1000 a month – in addition to the unavoidable expenses back in Australia. There had to be a better way. A modest pied-à-terre perhaps?

Understandably, our daughter wanted us close to her and the family, in or around Bath. Our son-in-law tried to interest us in Jane Austen’s former basement but the appeal of reading ‘Pride and Prejudice’ in authentic period gloom was limited and brief. The other possibility was somewhere outside the UK but within reasonable flying time of nearby Bristol Airport… somewhere close to, say, Bergerac Airport.

In May 2012 we found ourselves in Monpazier, that most perfect of bastides in the Dordogne, just over the border from the Lot-et-Garonne. We called in on Annette, an estate agent we knew.

‘I’ve something that might interest you…’, she said. Ominous words.

The building of which the house formed the middle section had once been a hotel – some say a brothel – before being converted into separate units. The exterior was uninviting; anonymity had evidently been a requirement of the building’s alleged former function. The interior, though, was a revelation… The developer had punched out walls, changed levels and made the twisting 250-year old central staircase an open-plan feature of both the ground- and first- floors. But the biggest surprise, tucked away at the back, was a walled courtyard – a sought-after rarity in the heart of a medieval village.

Cursing our good fortune, we made an offer… then another… until finally the deal was done. It cost half Miss Austen’s dark, damp basement.

So who has changed – us or the French?

Both I suspect. We’ve come to appreciate what we had… lost… and missed. But the French too seem to have mellowed. Whether it’s the high unemployment, the divisive immigration debate or the sight of their young people seeking success across the Channel… the sharp edges have been rubbed off the old Gallic certainties of the Mitterrand and Chirac years. There seems to be more self-questioning. Even self-doubt.

With the occasional heart-warming exception… One morning, sipping coffee in our arcaded square in Monpazier, I listen in disbelief as another resident, an ex-Parisian, remarks that France is the only country in the world which she can imagine devoting a television programme to books and reading.

It’s good to be back.

As the next article, the third, makes clear, we would soon commit ourselves even further. Sadly, though, it didn't last. Read on...

THE CONNEXION

MARCH, 2020

Michael Delahaye and his wife Anni have moved to France not once but twice - first from the UK, then from Australia. Now they are back in Australia. He explains whey they've left again...

It was last summer, a Sunday in late August. As I looked through the open windows, beyond the rose-fringed terrace, to the valley marking the frontline of the Hundred Years War, the truth hit me: ‘We are going to have to leave.’ Just seven words, but they were the culmination of an association with France that went back more than three decades.

MARCH, 2020

Michael Delahaye and his wife Anni have moved to France not once but twice - first from the UK, then from Australia. Now they are back in Australia. He explains whey they've left again...

It was last summer, a Sunday in late August. As I looked through the open windows, beyond the rose-fringed terrace, to the valley marking the frontline of the Hundred Years War, the truth hit me: ‘We are going to have to leave.’ Just seven words, but they were the culmination of an association with France that went back more than three decades.

In 1988 we bought our first holiday home in a tiny hill-top village in the Lot-et-Garonne. La vie française was everything we had hoped for but within a decade we had – no other way to put it – fallen out of love with France and the French. We sold up and, after a few years back in the UK, emigrated to Australia, my wife’s homeland. France, the old seductress, has a way of drawing one back. During a European trip in 2013 revisiting old haunts, we bought a small pied-à-terre in the Dordogne. Within three years, we had left Australia and formally taken up French residency, signing up to the health system, the tax regime… and moving into a bigger house which we imagined would be our permanent home for years to come. After all, we had been here before and learned the lessons.

But the rules of being a permanent resident are not the same as those for a second-home owner…

Our new base was that most perfect of medieval bastides, Monpazier. Founded in 1284 by English King Edward 1st, its current population is about 530 - with a high proportion of expats: Dutch, German, American, Antipodean and, this being ‘Dordogneshire’, British.

One of our first acts was to present ourselves to the Mayor. Wishing to be an active citizen and having a reasonable command of French, I volunteered my services as a translator. A few days later, an expat local sidled up to me and, in the hushed tones of one compelled to give painful advice, told me it had been noticed that I had ‘joined the Mayor’s camp’. This was followed by another expat complaining that I seemed to be ‘into everything’ – a way of saying that I hadn’t served the social apprenticeship required of a newcomer.

Lesson 1: Joining a small community is like going to a new school: in making some friends, you will forfeit others.

Though irritating, it was a minor rite of passage. Discovering that there was no up-to-date English guidebook of the village, despite its estimated 250,000 visitors a year, I put together a virtual one on-line and was soon asked to conduct the occasional tour for Anglophone visitors. My wife, meanwhile, joined the judging panel of the annual ‘maisons fleuries’ competition. Within a year, we couldn’t walk through the village without half a dozen double-kisses along the way. So far as the locals were concerned, we were bien intégrés.

But integration requires communication…

Lesson 2: As a permanent resident, you have to deal with officials, doctors, accountants, car mechanics, etc. – in their language and sometimes over the phone. Don’t expect to get by with the ‘shopping French’ of a visitor.

One of the biggest helps, we found, was to eschew the satellite dish and watch only terrestrial French TV channels, most of which are helpfully sub-titled, in French. It may sound a bit ‘swotty’ but, with a notepad to hand, there is no better way to build up new and refresh old vocabulary. And don’t believe those who rubbish French television. Particularly recommended is the excellent 20h00 evening news on France 2.

“But what about all that ghastly bureaucracy?’’, visiting friends would ask. There is no denying it can be tedious but…

Lesson 3: The French are masters of the creative interpretation of their own rules.

One example among many… Leaving a Bergerac hypermarket one rainy day, I dropped a 40 Euros bottle of whisky, bought as a gift, in the car park. Resisting the temptation to lick the asphalt, I went back inside to check whether the company had insurance cover for such eventualities. The deputy manager was sympathetic but no, their policy didn’t extend beyond the building. Five minutes later, as I queued up with a replacement, another 40 euros grudgingly in hand, the manager herself appeared. ‘Just take it,’ she whispered, ‘We’ll sort it out…’

By now you’re probably guessing that the only reason for our leaving has to be Brexit.

Not so. Psychologically, it came as a blow to realise we no longer ‘belonged’ in France but we could have accepted the administrative complexities and the possible extra cost of health care.

Ultimately, our decision came down to the realisation that to Liberté and Égalité might soon be added Austérité. Our financial base was still in Australia but French taxation is global. This meant income from our Australian Super Fund pensions, which in Australia is tax-free to encourage self-sufficiency in later life, was now taxed. Fair enough, you may say; the level of taxation goes with the territory you choose to live in.

But the rules of being a permanent resident are not the same as those for a second-home owner…

Our new base was that most perfect of medieval bastides, Monpazier. Founded in 1284 by English King Edward 1st, its current population is about 530 - with a high proportion of expats: Dutch, German, American, Antipodean and, this being ‘Dordogneshire’, British.

One of our first acts was to present ourselves to the Mayor. Wishing to be an active citizen and having a reasonable command of French, I volunteered my services as a translator. A few days later, an expat local sidled up to me and, in the hushed tones of one compelled to give painful advice, told me it had been noticed that I had ‘joined the Mayor’s camp’. This was followed by another expat complaining that I seemed to be ‘into everything’ – a way of saying that I hadn’t served the social apprenticeship required of a newcomer.

Lesson 1: Joining a small community is like going to a new school: in making some friends, you will forfeit others.

Though irritating, it was a minor rite of passage. Discovering that there was no up-to-date English guidebook of the village, despite its estimated 250,000 visitors a year, I put together a virtual one on-line and was soon asked to conduct the occasional tour for Anglophone visitors. My wife, meanwhile, joined the judging panel of the annual ‘maisons fleuries’ competition. Within a year, we couldn’t walk through the village without half a dozen double-kisses along the way. So far as the locals were concerned, we were bien intégrés.

But integration requires communication…

Lesson 2: As a permanent resident, you have to deal with officials, doctors, accountants, car mechanics, etc. – in their language and sometimes over the phone. Don’t expect to get by with the ‘shopping French’ of a visitor.

One of the biggest helps, we found, was to eschew the satellite dish and watch only terrestrial French TV channels, most of which are helpfully sub-titled, in French. It may sound a bit ‘swotty’ but, with a notepad to hand, there is no better way to build up new and refresh old vocabulary. And don’t believe those who rubbish French television. Particularly recommended is the excellent 20h00 evening news on France 2.

“But what about all that ghastly bureaucracy?’’, visiting friends would ask. There is no denying it can be tedious but…

Lesson 3: The French are masters of the creative interpretation of their own rules.

One example among many… Leaving a Bergerac hypermarket one rainy day, I dropped a 40 Euros bottle of whisky, bought as a gift, in the car park. Resisting the temptation to lick the asphalt, I went back inside to check whether the company had insurance cover for such eventualities. The deputy manager was sympathetic but no, their policy didn’t extend beyond the building. Five minutes later, as I queued up with a replacement, another 40 euros grudgingly in hand, the manager herself appeared. ‘Just take it,’ she whispered, ‘We’ll sort it out…’

By now you’re probably guessing that the only reason for our leaving has to be Brexit.

Not so. Psychologically, it came as a blow to realise we no longer ‘belonged’ in France but we could have accepted the administrative complexities and the possible extra cost of health care.

Ultimately, our decision came down to the realisation that to Liberté and Égalité might soon be added Austérité. Our financial base was still in Australia but French taxation is global. This meant income from our Australian Super Fund pensions, which in Australia is tax-free to encourage self-sufficiency in later life, was now taxed. Fair enough, you may say; the level of taxation goes with the territory you choose to live in.

But the additional problem for us was that for decades I have worked as a freelance, my income fluctuating wildly from year to year, even month to month. Last year our always-helpful French accountant warned that my ‘activity’ was such that I could be re-classified as a ‘self-employed professional’ – and, with it, more paperwork and still more tax. As to how this ‘activity’ was calculated – the number of weeks worked, the amount of euros earned? - that would be for a local tax officer to decide, year on year. A fiscal sword would always be hanging over us… on the finest of threads.

Lesson 4: Interpretation of the rules doesn’t always work to one’s advantage.

The clincher, though, was France’s inheritance law, the Droits de Succession. Many of us took comfort when in 2015 France implemented the EU regulation allowing foreign residents to choose their own national inheritance law when deciding who would get what of their estate. What some of us chose to overlook was that the tax element of French inheritance law, death duties, remained unchanged.

To quote the website of the international tax advisers, Blevins Franks: “Succession tax can therefore be quite crippling, potentially reducing the inheritance you hoped to leave to someone by over half… For couples with children from previous relationships this can be a real problem”.

That was us. Our daughter – my step-daughter – would be the beneficiary of our estate. If she inherited from me as the surviving parent, she would face 60% inheritance tax. Australia, by contrast, has no inheritance tax.

So, like much else, our decision came down to death and taxes. But, channelling my inner Edith Piaf, no regrets. The last four years have been incredibly enriching – a chance to live in another culture and, metaphorically, another skin; in a film-set medieval village that oozes history from every stone.

We may have paid for the privilege but, looked at another way, it has been an experience money couldn’t buy.

Lesson 4: Interpretation of the rules doesn’t always work to one’s advantage.

The clincher, though, was France’s inheritance law, the Droits de Succession. Many of us took comfort when in 2015 France implemented the EU regulation allowing foreign residents to choose their own national inheritance law when deciding who would get what of their estate. What some of us chose to overlook was that the tax element of French inheritance law, death duties, remained unchanged.

To quote the website of the international tax advisers, Blevins Franks: “Succession tax can therefore be quite crippling, potentially reducing the inheritance you hoped to leave to someone by over half… For couples with children from previous relationships this can be a real problem”.

That was us. Our daughter – my step-daughter – would be the beneficiary of our estate. If she inherited from me as the surviving parent, she would face 60% inheritance tax. Australia, by contrast, has no inheritance tax.

So, like much else, our decision came down to death and taxes. But, channelling my inner Edith Piaf, no regrets. The last four years have been incredibly enriching – a chance to live in another culture and, metaphorically, another skin; in a film-set medieval village that oozes history from every stone.

We may have paid for the privilege but, looked at another way, it has been an experience money couldn’t buy.

THE CONNEXION

JANUARY, 2016

BUT WHAT DO THEY REALLY THINK OF US?

When asked about their feelings towards foreigners, the French typically respond with clichés - so Michael Delahaye has been digging deeper to learn the truth...

JANUARY, 2016

BUT WHAT DO THEY REALLY THINK OF US?

When asked about their feelings towards foreigners, the French typically respond with clichés - so Michael Delahaye has been digging deeper to learn the truth...

Nations do it; individuals do it – we all construct self-serving narratives. Brits living in France are no exception.

Our narrative goes like this: We are British, they are French; but a few centuries back this was as much our land as theirs. Swathes of the country – notably the south-west and a hunk of the north coast – belonged to the English crown (yes, at this point ‘British’ has morphed into ‘English’).

So we belong. You might almost say we have ‘a right of return’. Which is why we are particularly cheered when we come across a Frenchman named Edouard –after an English king called Edward.

Rather more nuanced is how our French hosts regard us. We are after all cuckoos – or, if owners of holiday homes, swallows who most of the year leave our nests empty or occupied by a succession of strangers. Before we bought our first French house, in the Lot-et-Garonne back in the mid-1980s, we checked out the likely reaction of our potential neighbours. The first exclaimed, ‘Alors, vous êtes revenus dans votre coin!’ (loosely translated, ‘You’ve come home’), a reference to Aquitaine having been English-owned for three hundred years.

Pumped up, we introduced ourselves to other locals. Their reaction was probably more honest: ‘Eh bien, better you for a couple of months of the year than Parisians every weekend…’ (We thought of naming our house, ‘Faute de Mieux’ ). Regardless, we continued our stately progress to the end of the village and were delighted to find there an ancient stone gate proudly announcing itself as La Porte des Anglais. ‘Et voilà’, we thought – home indeed! A curious local, observing our proprietorial grins, explained that it had been so named because ‘That was where we fought you lot off back in the thirteen hundreds’.

OK, so we are gate-crashers – but at least we bring something to the party: cash.

I put this to an anglophile neighbour. ‘Ah,’ he said, raising a finger, ‘More than that! Not only will you give me mad money for my mother’s tumbledown ruin but you will do it up exquisitely, in the best possible taste…’ A second finger appeared. ‘And you will employ local labour – so you are supporting our economy…’ A third finger. ‘The result is that it is you British who are helping to preserve our architectural heritage. Je vous remercie, Monsieur!’

Well, jusqu’à un certain point. We don’t always use local labour. Sometimes we bring over George from south London with his mate who will happily combine a couple of weeks’ holiday sur le cont-ee-nong with a bit of cash-in-hand work. All for a fraction of what it would cost using the local Didier.

The French accept this – free movement of labour is a fundamental tenet of the EU – but don’t expect them to like it. Just as they still loyally buy Renaults, Peugeots and Citroëns, there’s a strong national feeling that you should support your local artisans. It’s why the DIY revolution was late to take off in France and one reason that a tart bought from a pâtisserie is generally more acceptable at the end of a meal than something home-made, however delicious.

That said, we do make an effort to integrate. Yes, there are the unreconstructed ex-pats who seem to take a pride in not learning the language but, with a younger influx, that is changing. Most Brits in my experience try to speak French and, although they may still play cricket (the English at least), they also join the village choir, tennis club or rambling group and even get involved in local politics.

Yet when it comes to one-on-one social interaction, we can be slow-learners. We’re not good at ‘presenting’ ourselves - possibly because, unlike the French, we’re not taught it as children. Any shopkeeper will tell you about the Brits who walk into their shops, heads down, pick over a few items and then leave without so much as un petit Bonjour.

The way we regulate our family relations is equally puzzling to our hosts. I once had to explain to an incredulous official that the British did not have, didn’t even understand the concept of, a ‘livret de famille’, (the official family booklet recording marriages and offspring), doubtless confirming his suspicion that we were a nation of fornicators and bastards. You’re likely to get the same reaction if, as a married couple, you try to open a bank account but with the wife wanting to use her maiden or professional name for cards and cheques.

We are, as one French friend put it, like a species of non-native wildlife - undeniably invasive but always worthy of study. And, though generally benign, occasionally provocative…

During the summer the London-based open-air theatre company Antic Disposition toured Perigord and Quercy with Shakespeare’s ‘Henry V’. Although it had been tactfully re-imagined as a joint production by Anglo-French troops in a WW1 field hospital, it remains a ‘confronting’ play – the more so this being the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt.

So it was an electrifying moment when Henry was raised high by his band of brothers and his words, ‘Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more; or close the wall up with our English dead!’, ricocheted around Monpazier’s Place des Cornières. I’m sure I wasn’t the only member of the predominantly British audience wondering whether a band of French producteurs and éleveurs might appear and dump a heap of steaming ordure on the stage.

But no. By the end of the play, with the reconciliatory marriage of Henry to the French king’s daughter, the feeling can best be described as warm and fuzzy. At one point Shakespeare has a character describe France as ‘this best garden of the world’ and this surely is what ultimately binds us: that our hosts appreciate how much we appreciate their incomparably beautiful country.

So much so, we want them to share it with us.

Our narrative goes like this: We are British, they are French; but a few centuries back this was as much our land as theirs. Swathes of the country – notably the south-west and a hunk of the north coast – belonged to the English crown (yes, at this point ‘British’ has morphed into ‘English’).

So we belong. You might almost say we have ‘a right of return’. Which is why we are particularly cheered when we come across a Frenchman named Edouard –after an English king called Edward.

Rather more nuanced is how our French hosts regard us. We are after all cuckoos – or, if owners of holiday homes, swallows who most of the year leave our nests empty or occupied by a succession of strangers. Before we bought our first French house, in the Lot-et-Garonne back in the mid-1980s, we checked out the likely reaction of our potential neighbours. The first exclaimed, ‘Alors, vous êtes revenus dans votre coin!’ (loosely translated, ‘You’ve come home’), a reference to Aquitaine having been English-owned for three hundred years.

Pumped up, we introduced ourselves to other locals. Their reaction was probably more honest: ‘Eh bien, better you for a couple of months of the year than Parisians every weekend…’ (We thought of naming our house, ‘Faute de Mieux’ ). Regardless, we continued our stately progress to the end of the village and were delighted to find there an ancient stone gate proudly announcing itself as La Porte des Anglais. ‘Et voilà’, we thought – home indeed! A curious local, observing our proprietorial grins, explained that it had been so named because ‘That was where we fought you lot off back in the thirteen hundreds’.

OK, so we are gate-crashers – but at least we bring something to the party: cash.

I put this to an anglophile neighbour. ‘Ah,’ he said, raising a finger, ‘More than that! Not only will you give me mad money for my mother’s tumbledown ruin but you will do it up exquisitely, in the best possible taste…’ A second finger appeared. ‘And you will employ local labour – so you are supporting our economy…’ A third finger. ‘The result is that it is you British who are helping to preserve our architectural heritage. Je vous remercie, Monsieur!’

Well, jusqu’à un certain point. We don’t always use local labour. Sometimes we bring over George from south London with his mate who will happily combine a couple of weeks’ holiday sur le cont-ee-nong with a bit of cash-in-hand work. All for a fraction of what it would cost using the local Didier.

The French accept this – free movement of labour is a fundamental tenet of the EU – but don’t expect them to like it. Just as they still loyally buy Renaults, Peugeots and Citroëns, there’s a strong national feeling that you should support your local artisans. It’s why the DIY revolution was late to take off in France and one reason that a tart bought from a pâtisserie is generally more acceptable at the end of a meal than something home-made, however delicious.

That said, we do make an effort to integrate. Yes, there are the unreconstructed ex-pats who seem to take a pride in not learning the language but, with a younger influx, that is changing. Most Brits in my experience try to speak French and, although they may still play cricket (the English at least), they also join the village choir, tennis club or rambling group and even get involved in local politics.

Yet when it comes to one-on-one social interaction, we can be slow-learners. We’re not good at ‘presenting’ ourselves - possibly because, unlike the French, we’re not taught it as children. Any shopkeeper will tell you about the Brits who walk into their shops, heads down, pick over a few items and then leave without so much as un petit Bonjour.

The way we regulate our family relations is equally puzzling to our hosts. I once had to explain to an incredulous official that the British did not have, didn’t even understand the concept of, a ‘livret de famille’, (the official family booklet recording marriages and offspring), doubtless confirming his suspicion that we were a nation of fornicators and bastards. You’re likely to get the same reaction if, as a married couple, you try to open a bank account but with the wife wanting to use her maiden or professional name for cards and cheques.

We are, as one French friend put it, like a species of non-native wildlife - undeniably invasive but always worthy of study. And, though generally benign, occasionally provocative…

During the summer the London-based open-air theatre company Antic Disposition toured Perigord and Quercy with Shakespeare’s ‘Henry V’. Although it had been tactfully re-imagined as a joint production by Anglo-French troops in a WW1 field hospital, it remains a ‘confronting’ play – the more so this being the 600th anniversary of the Battle of Agincourt.

So it was an electrifying moment when Henry was raised high by his band of brothers and his words, ‘Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more; or close the wall up with our English dead!’, ricocheted around Monpazier’s Place des Cornières. I’m sure I wasn’t the only member of the predominantly British audience wondering whether a band of French producteurs and éleveurs might appear and dump a heap of steaming ordure on the stage.

But no. By the end of the play, with the reconciliatory marriage of Henry to the French king’s daughter, the feeling can best be described as warm and fuzzy. At one point Shakespeare has a character describe France as ‘this best garden of the world’ and this surely is what ultimately binds us: that our hosts appreciate how much we appreciate their incomparably beautiful country.

So much so, we want them to share it with us.

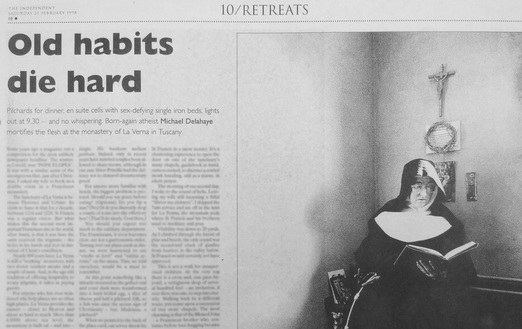

THE INDEPENDENT, 5 SEPTEMBER 1999

Photo: Karen Robinson

Pilchards for dinner, en suite cells with sex-defying single iron beds, lights out at 9.30 - and no whispering. Born-again atheist Michael Delahaye mortifies the flesh at the monastery of La Verna in Tuscany

Some years ago a magazine ran a competition for the most unlikely newspaper headline. The winner, as I recall, was "POPE ELOPES". It was with a similar sense of the incongruous that, just after Christmas, I asked my wife to book us a double room in a Franciscan monastery.

The Sanctuary of La Verna is between Florence and Urbino. Its claim to fame is that for a decade, between 1214 and 1224, St Francis was a regular visitor. But what makes this the second most important Franciscan site in the world, after Assisi, is that it was here the saint received the stigmata - the holes in his hands and feet in imitation of Christ's crucifixion. Nearly 800 years later, La Verna is still a 'working' monastery, with two dozen resident monks and a couple of nuns. And, in the age-old tradition of offering hospitality to weary pilgrims, it takes in paying guests.

For anyone who has ever wondered why holy places are so often high places, La Verna provides the answer - closer to Heaven and about as hard to reach. More than 4,000 feet above sea level, the monastery is built on - and into - an extraordinary outcrop of rock. During the winter months it's literally lost in the clouds. As you approach through a forest dripping with moisture, up a series of increasingly tight switch-backs, it's hard not to feel like the unsuspecting Jonathan Harker in one of those early Dracula movies.

The night we arrived, Sister Priscilla was on reception, swathed in black anorak and white scarf. She referred to the bookings list... 'Ah, numero ventisei'. Room 26 turned out to be an 'en suite cell', 10ft by 10, with a pair of single beds; shower and lavatory. It was clean and adequate, although during the night my wife was to develop a peculiar devotion to the cast-iron radiator. On the back of the door was an injunction against whispering and giggling after 10pm.

For a number of reasons, this is not a place for honeymoon couples. All beds are narrow and chastely single. Hic hankum nullum pankum. Indeed, only in recent years have married couples been allowed to share rooms, although in our case Sister Priscilla had the delicacy not to demand documentary proof.

For anyone more familiar with hotels, the biggest problem is protocol. Should you say grace before eating? (Optional) Do you tip a nun? (No) Or do you discreetly drop a couple of coins into the offertory box? (That'll do nicely. God bless.)

Nor should you expect too much in the culinary department. The Franciscans, it soon becomes clear, are not a gastronomic order. Turning over our place-cards at dinner, we were heartened to see vitello ai ferri and anitra arrosto on the menu. This, we told ourselves, would be a meal to remember. At this point something like a miracle occurred as the grilled veal and roast duck were transformed into a hard boiled egg, a slice of cheese and half a pilchard. OK, so a fish was once the secret sign of Christianity - but, Madonna, a pilchard?

When we pointed to the back of the place-card, our server shook his head: 'That's the summer menu. This is winter.' A diner at the next table murmured 'Buon appetito', thoughtfully adding, 'Good hunger!'.

Dinner over, we were about to settle in with a compensatory glass of the monastery's excellent Lamponi - a diabolically tempting 33 degree proof raspberry liqueur - when we were sent to bed. Lights out, doors locked, heating off. Buona Notte. It was 9.30pm.

None of this is to diminish the power of the place. You might even argue it helps concentrate the mind. La Verna is Gethsemane without the coaches; Lourdes minus the plaster knick-knackery. As a born-again atheist, I'm hardly qualified to judge but I've no doubt that anyone seeking 'the spirit of St Francis' is more likely to find it here than at Assisi (of which my clearest memory is buying our daughter a plastic globe of St Francis in a snow storm). It's a chastening experience to open the door on one of the sanctuary's many chapels, guidebook in hand, camera cocked, to discover a cowled monk kneeling, still as a statue, in silent prayer.

The morning of our second day, I woke to the sound of bells. Leaving my wife still incanting a fitful 'Shiver me cloisters', I skipped the 7am service and set off in the mist for La Penna, the mountain peak where St Francis and his brethren used to meditate and pray. Visibility was down to 20 yards. As I climbed through the forest of pine and beech, the only sound was the occasional crack of gunfire from hunters in the valley below. St Francis would certainly not have approved.

This is not a walk for unsupervised children. At the very top there is a cross and, one pace beyond, a vertiginous drop of several hundred feet - an invitation, if ever there was one, to step into eternity. Walking back by a different route, you come upon a succession of tiny stone chapels. The most charming is that of the Blessed John - a Franciscan brother who, centuries before tree-hugging became fashionable, spent his days praying in front of a giant beech. When the tree died, the chapel with its low-walled courtyard was built in its place.

Back in the monastery, there are more than a dozen della Robbia glazed reliefs. The best is in the Basilica - a stunning Annunciation by Andrea della Robbia. In the Chapel of the Blessed Stigmata, before a Crucifixion by Andrea, you can see the stone on which St Francis received his wounds.

You don't have to be religious to appreciate La Verna, but it probably helps. If, as a bonus, you fancy a foretaste of Purgatory, make the trip in winter. On the other hand, it's telling that St Francis himself seems to have come here only during the summer months.

Santuario della Verna, 52010 Chiusi della Verna, la Toscana (00 39 575 5341) Full board: 62,000 lire per person (approx pounds 22)

Photo: Karen Robinson

Pilchards for dinner, en suite cells with sex-defying single iron beds, lights out at 9.30 - and no whispering. Born-again atheist Michael Delahaye mortifies the flesh at the monastery of La Verna in Tuscany

Some years ago a magazine ran a competition for the most unlikely newspaper headline. The winner, as I recall, was "POPE ELOPES". It was with a similar sense of the incongruous that, just after Christmas, I asked my wife to book us a double room in a Franciscan monastery.

The Sanctuary of La Verna is between Florence and Urbino. Its claim to fame is that for a decade, between 1214 and 1224, St Francis was a regular visitor. But what makes this the second most important Franciscan site in the world, after Assisi, is that it was here the saint received the stigmata - the holes in his hands and feet in imitation of Christ's crucifixion. Nearly 800 years later, La Verna is still a 'working' monastery, with two dozen resident monks and a couple of nuns. And, in the age-old tradition of offering hospitality to weary pilgrims, it takes in paying guests.

For anyone who has ever wondered why holy places are so often high places, La Verna provides the answer - closer to Heaven and about as hard to reach. More than 4,000 feet above sea level, the monastery is built on - and into - an extraordinary outcrop of rock. During the winter months it's literally lost in the clouds. As you approach through a forest dripping with moisture, up a series of increasingly tight switch-backs, it's hard not to feel like the unsuspecting Jonathan Harker in one of those early Dracula movies.

The night we arrived, Sister Priscilla was on reception, swathed in black anorak and white scarf. She referred to the bookings list... 'Ah, numero ventisei'. Room 26 turned out to be an 'en suite cell', 10ft by 10, with a pair of single beds; shower and lavatory. It was clean and adequate, although during the night my wife was to develop a peculiar devotion to the cast-iron radiator. On the back of the door was an injunction against whispering and giggling after 10pm.

For a number of reasons, this is not a place for honeymoon couples. All beds are narrow and chastely single. Hic hankum nullum pankum. Indeed, only in recent years have married couples been allowed to share rooms, although in our case Sister Priscilla had the delicacy not to demand documentary proof.

For anyone more familiar with hotels, the biggest problem is protocol. Should you say grace before eating? (Optional) Do you tip a nun? (No) Or do you discreetly drop a couple of coins into the offertory box? (That'll do nicely. God bless.)

Nor should you expect too much in the culinary department. The Franciscans, it soon becomes clear, are not a gastronomic order. Turning over our place-cards at dinner, we were heartened to see vitello ai ferri and anitra arrosto on the menu. This, we told ourselves, would be a meal to remember. At this point something like a miracle occurred as the grilled veal and roast duck were transformed into a hard boiled egg, a slice of cheese and half a pilchard. OK, so a fish was once the secret sign of Christianity - but, Madonna, a pilchard?

When we pointed to the back of the place-card, our server shook his head: 'That's the summer menu. This is winter.' A diner at the next table murmured 'Buon appetito', thoughtfully adding, 'Good hunger!'.

Dinner over, we were about to settle in with a compensatory glass of the monastery's excellent Lamponi - a diabolically tempting 33 degree proof raspberry liqueur - when we were sent to bed. Lights out, doors locked, heating off. Buona Notte. It was 9.30pm.

None of this is to diminish the power of the place. You might even argue it helps concentrate the mind. La Verna is Gethsemane without the coaches; Lourdes minus the plaster knick-knackery. As a born-again atheist, I'm hardly qualified to judge but I've no doubt that anyone seeking 'the spirit of St Francis' is more likely to find it here than at Assisi (of which my clearest memory is buying our daughter a plastic globe of St Francis in a snow storm). It's a chastening experience to open the door on one of the sanctuary's many chapels, guidebook in hand, camera cocked, to discover a cowled monk kneeling, still as a statue, in silent prayer.

The morning of our second day, I woke to the sound of bells. Leaving my wife still incanting a fitful 'Shiver me cloisters', I skipped the 7am service and set off in the mist for La Penna, the mountain peak where St Francis and his brethren used to meditate and pray. Visibility was down to 20 yards. As I climbed through the forest of pine and beech, the only sound was the occasional crack of gunfire from hunters in the valley below. St Francis would certainly not have approved.

This is not a walk for unsupervised children. At the very top there is a cross and, one pace beyond, a vertiginous drop of several hundred feet - an invitation, if ever there was one, to step into eternity. Walking back by a different route, you come upon a succession of tiny stone chapels. The most charming is that of the Blessed John - a Franciscan brother who, centuries before tree-hugging became fashionable, spent his days praying in front of a giant beech. When the tree died, the chapel with its low-walled courtyard was built in its place.

Back in the monastery, there are more than a dozen della Robbia glazed reliefs. The best is in the Basilica - a stunning Annunciation by Andrea della Robbia. In the Chapel of the Blessed Stigmata, before a Crucifixion by Andrea, you can see the stone on which St Francis received his wounds.

You don't have to be religious to appreciate La Verna, but it probably helps. If, as a bonus, you fancy a foretaste of Purgatory, make the trip in winter. On the other hand, it's telling that St Francis himself seems to have come here only during the summer months.

Santuario della Verna, 52010 Chiusi della Verna, la Toscana (00 39 575 5341) Full board: 62,000 lire per person (approx pounds 22)

THE IRISH INDEPENDENT, 3 NOVEMBER 2012

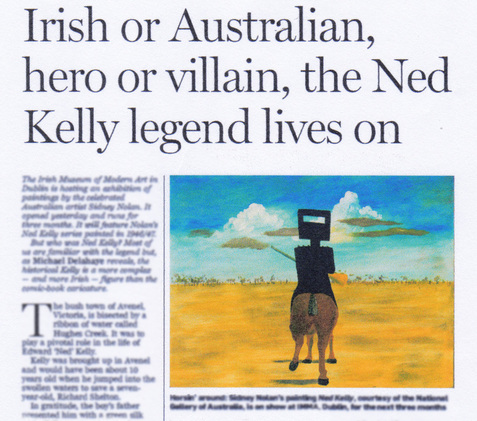

Sidney Nolan picture: The National Gallery, Canberra

The Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin is hosting an exhibition of paintings by the celebrated Australian artist Sidney Nolan, opening 2nd November and running for three months. It will feature Nolan’s Ned Kelly series painted in 1946/47.

But who was Ned Kelly? Most of us are familiar with the legend but, as Michael Delahaye reveals, the historical Kelly is a more complex - and more Irish - figure than the comic-book caricature.

The bush town of Avenel, Victoria, is bisected by a ribbon of water called Hughes Creek. It was to play a pivotal role in the life of Edward ‘Ned’ Kelly. Kelly was brought up in Avenel and would have been about ten years old when he jumped into the swollen waters to save a seven-year-old, Richard Shelton. In gratitude, the boy’s father presented him with a green silk sash. Kelly treasured it for the rest of his life and wrapped it round his body like a protective talisman for the final shoot-out at Glenrowan.

Today the sash is enshrined in a glass case at the Benalla Costume & Pioneer Museum. Darkly stained with Ned’s blood, it is the ultimate Kelly relic. There can't be many Irish visitors who, viewing it, don't hear 'The wearing of the green'. And therein lies the key to Kelly – his Irishness.

Despite this, Australians like to think of Ned Kelly as one of theirs. Old bucket head is right up there with the koala and the kanga – an Aussie icon of the first order. And for countless Australian males he’s something more: the embodiment of two things they hold particularly dear…

First, ‘mateship’. When the final shoot-out came, Ned chose to confront the police, all barrels blazing, rather than abandon his friends. Second, he was what Australians call a ‘larrikin’ – a bit of a lad who ‘larks around’ and shows scant respect for authority.

And of course no-one fixed the maverick Kelly more memorably in the Australian landscape - and consciousness - than the artist Sidney Nolan, setting Ned’s hallmark helmet starkly against the arid outback.

Yet Kelly was hanged – he was just twenty-five years old - two decades before Australia became a single, federated nation in 1901. Born in the Colony of Victoria, he was of Irish parentage on both sides. His father, John, had been transported from Moyglass, County Tipperary, for stealing pigs, while the family of his mother, Ellen (née Quinn), had emigrated when she was still a child. And, tellingly, we know that Ned himself spoke with an Irish brogue.

Starting out as a horse thief, Kelly went on to rob banks and kill cops. But, once outlawed by the colonial authorities, he became something of a guerrilla revolutionary, a champion of the impoverished immigrant population in north-eastern Victoria. More Robin Hood than Billy the Kid.

And not just in his own eyes; for two years a network of local sympathisers, possibly hundreds, provided the Kelly Gang with food, shelter, stabling and, most important, silent collusion.

Kelly may have been an Irish Catholic but, as Ian Jones, the widely acknowledged authority on the Kelly Gang, points out: “Many of his friends were Protestant. His mother married a Protestant (after the death of Ned’s father). Two of his sisters married Protestants. There were Englishmen – Cornishmen - very supportive of him.”

Kelly’s closest gang associate was his lieutenant, Joe Byrne. Of Irish rebel stock, Byrne had a natural socio-political bent. Before one of their bank raids, the two men composed a 56-page proclamation, the Jerilderie Letter. In part, it’s a justification for their criminal behaviour. But it’s also a Fenian manifesto – a demand for justice and equality, put in the context of the centuries-old struggle to, quote, “rise old Erins Isle once more from the pressure and tyrannism of the English yoke which has kept it in poverty and starvation...”

Jones believes that the ultimate intention was nothing less than the establishment of an independent ‘Republic of North-Eastern Victoria’. So could there today have been a green flag flying over an Irish enclave in the modern State of Victoria? Jones cites an intriguing parallel: the First Boer War in South Africa, also coincidentally at the end of the nineteenth century: “It was a farmers’ rebellion against British rule, in which farmers rode their horses and had their own rifles and used their intimate knowledge of the land to combat the English.” In the Kelly Gang’s corner of Victoria, says Jones, “you had the best shots, the best horsemen and the best bushmen the colonies could produce… Imagine a little army of men like that...”

The extent of Kelly’s Irishness is of more than historical interest. It’s become a hot topical issue since the discovery in 2009, and subsequent DNA verification, of his bones in an unmarked prison grave. Earlier this year the Victorian State Government decided they should be handed over to his family. Complications arise because ‘the family’ now comprises several hundred members through half a dozen separate lines – both Catholic and Protestant, Irish and non-Irish. Several months’ consultation lies ahead.

If the bones are to be buried among Kelly’s relatives, as seems likely, what sort of public commemoration would be appropriate? Given that Kelly was both a Catholic and a self-confessed killer, should he be accorded a requiem mass? Kelly, who by all accounts played ‘the gentleman bushranger’ with charm and humour, would doubtless be amused. 132 years after his death, he is still making news.

Michael Delahaye's film about Ned Kelly will be broadcast by RTE’s NATIONWIDE programme on 16th January 2013

POSTSCRIPT:

As predicted, the burial of the bones turned out to be a bruising and divisive affair, with the various branches of the extended ‘Kelly Family’ splitting along Catholic/Protestant lines. In the end the Catholic members won the day, any hope of consultation or consensus having evaporated early on. A full Requiem Mass was duly held at St Patrick’s Church, Wangaratta, on 18th January 2013, followed by a ‘private’ burial at Greta Cemetery, North Victoria, from which the media were excluded. To thwart souvenir hunters, Kelly’s bones were buried beneath a slab of concrete in an unmarked grave, not far from those of his mother and brother.

Sidney Nolan picture: The National Gallery, Canberra

The Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin is hosting an exhibition of paintings by the celebrated Australian artist Sidney Nolan, opening 2nd November and running for three months. It will feature Nolan’s Ned Kelly series painted in 1946/47.

But who was Ned Kelly? Most of us are familiar with the legend but, as Michael Delahaye reveals, the historical Kelly is a more complex - and more Irish - figure than the comic-book caricature.

The bush town of Avenel, Victoria, is bisected by a ribbon of water called Hughes Creek. It was to play a pivotal role in the life of Edward ‘Ned’ Kelly. Kelly was brought up in Avenel and would have been about ten years old when he jumped into the swollen waters to save a seven-year-old, Richard Shelton. In gratitude, the boy’s father presented him with a green silk sash. Kelly treasured it for the rest of his life and wrapped it round his body like a protective talisman for the final shoot-out at Glenrowan.

Today the sash is enshrined in a glass case at the Benalla Costume & Pioneer Museum. Darkly stained with Ned’s blood, it is the ultimate Kelly relic. There can't be many Irish visitors who, viewing it, don't hear 'The wearing of the green'. And therein lies the key to Kelly – his Irishness.

Despite this, Australians like to think of Ned Kelly as one of theirs. Old bucket head is right up there with the koala and the kanga – an Aussie icon of the first order. And for countless Australian males he’s something more: the embodiment of two things they hold particularly dear…

First, ‘mateship’. When the final shoot-out came, Ned chose to confront the police, all barrels blazing, rather than abandon his friends. Second, he was what Australians call a ‘larrikin’ – a bit of a lad who ‘larks around’ and shows scant respect for authority.

And of course no-one fixed the maverick Kelly more memorably in the Australian landscape - and consciousness - than the artist Sidney Nolan, setting Ned’s hallmark helmet starkly against the arid outback.

Yet Kelly was hanged – he was just twenty-five years old - two decades before Australia became a single, federated nation in 1901. Born in the Colony of Victoria, he was of Irish parentage on both sides. His father, John, had been transported from Moyglass, County Tipperary, for stealing pigs, while the family of his mother, Ellen (née Quinn), had emigrated when she was still a child. And, tellingly, we know that Ned himself spoke with an Irish brogue.

Starting out as a horse thief, Kelly went on to rob banks and kill cops. But, once outlawed by the colonial authorities, he became something of a guerrilla revolutionary, a champion of the impoverished immigrant population in north-eastern Victoria. More Robin Hood than Billy the Kid.

And not just in his own eyes; for two years a network of local sympathisers, possibly hundreds, provided the Kelly Gang with food, shelter, stabling and, most important, silent collusion.

Kelly may have been an Irish Catholic but, as Ian Jones, the widely acknowledged authority on the Kelly Gang, points out: “Many of his friends were Protestant. His mother married a Protestant (after the death of Ned’s father). Two of his sisters married Protestants. There were Englishmen – Cornishmen - very supportive of him.”

Kelly’s closest gang associate was his lieutenant, Joe Byrne. Of Irish rebel stock, Byrne had a natural socio-political bent. Before one of their bank raids, the two men composed a 56-page proclamation, the Jerilderie Letter. In part, it’s a justification for their criminal behaviour. But it’s also a Fenian manifesto – a demand for justice and equality, put in the context of the centuries-old struggle to, quote, “rise old Erins Isle once more from the pressure and tyrannism of the English yoke which has kept it in poverty and starvation...”

Jones believes that the ultimate intention was nothing less than the establishment of an independent ‘Republic of North-Eastern Victoria’. So could there today have been a green flag flying over an Irish enclave in the modern State of Victoria? Jones cites an intriguing parallel: the First Boer War in South Africa, also coincidentally at the end of the nineteenth century: “It was a farmers’ rebellion against British rule, in which farmers rode their horses and had their own rifles and used their intimate knowledge of the land to combat the English.” In the Kelly Gang’s corner of Victoria, says Jones, “you had the best shots, the best horsemen and the best bushmen the colonies could produce… Imagine a little army of men like that...”

The extent of Kelly’s Irishness is of more than historical interest. It’s become a hot topical issue since the discovery in 2009, and subsequent DNA verification, of his bones in an unmarked prison grave. Earlier this year the Victorian State Government decided they should be handed over to his family. Complications arise because ‘the family’ now comprises several hundred members through half a dozen separate lines – both Catholic and Protestant, Irish and non-Irish. Several months’ consultation lies ahead.

If the bones are to be buried among Kelly’s relatives, as seems likely, what sort of public commemoration would be appropriate? Given that Kelly was both a Catholic and a self-confessed killer, should he be accorded a requiem mass? Kelly, who by all accounts played ‘the gentleman bushranger’ with charm and humour, would doubtless be amused. 132 years after his death, he is still making news.

Michael Delahaye's film about Ned Kelly will be broadcast by RTE’s NATIONWIDE programme on 16th January 2013

POSTSCRIPT:

As predicted, the burial of the bones turned out to be a bruising and divisive affair, with the various branches of the extended ‘Kelly Family’ splitting along Catholic/Protestant lines. In the end the Catholic members won the day, any hope of consultation or consensus having evaporated early on. A full Requiem Mass was duly held at St Patrick’s Church, Wangaratta, on 18th January 2013, followed by a ‘private’ burial at Greta Cemetery, North Victoria, from which the media were excluded. To thwart souvenir hunters, Kelly’s bones were buried beneath a slab of concrete in an unmarked grave, not far from those of his mother and brother.

THE FINANCIAL TIMES MAGAZINE, 11 NOVEMBER 2000

Illustration: Bruno Haward

COPING WITH CAPITALISM - IN GEORGIA

I am waiting for a taxi outside my guesthouse in the suburbs of Georgia's second city, Kutaisi. Taking a closer look at what I at first thought to be lamp standards, I realise they are trolley-bus gantries. But there is no sign of any trolley-bus. I ask the taxi driver about them. 'Oh, somebody shinned up the poles and stole the cable back in the early 1990s… Too expensive to replace them now.'

Time spent in the former Soviet - now democratic - Republic of Georgia is a kaleidoscopic experience, a jumble of vivid, but often contradictory, images that slip and slide into one another. Just when you think you have a handle on the place, it comes off in your hand.

For much of the day, there is no electricity. If you don't have a generator or can't afford the diesel to run one, you creep around with oil lamps. Driving between Kutaisi and the capital, Tbilisi, you pass the hulks of huge, Soviet-era factories, now silent and crumbling because they too have been starved of power. Between 1989 and 1998, Georgia's GDP plunged by two-thirds. The roads are now pitted and pot-holed . Diesel-belching buses zig-zag in search of asphalt. You begin to understand the importance of the word 'infrastructure'.

As we head down to the centre of Kutaisi, the taxi driver switches off the ignition to save petrol. It is a common practice in former Soviet countries - and potentially lethal. A couple of weeks earlier, according to my travelling companion, a local bus driver did the same. When he stepped on the brakes, there weren't any. Several children died.