NOTE: This website does not involve commercial transactions. Please ignore any 'Not Secure' tags.

Monpazier is an exquisite 'bastide' - a medieval fortified village - in the Dordogne, south-west France. Known as 'La Perle de l'Angleterre', it was founded in 1284 by the English king, Edward I. From early 2013 until January 2020, my wife Anni and I were fortunate - privileged - to be numbered among its population of around 530, which includes Brits, Dutch, Germans, Americans, South Africans, Australians and New Zealanders... in addition of course to the resident French who, with great generosity of spirit, tolerate all these foreigners in their midst.

Although we are now based in Australia, I continue to curate the website and update it as necessary with the help of friends and colleagues on the ground. If you click on Publications, then Articles, above, you will find a series of articles about our time in France, written for various newspapers over the 30 years of our association with the country.

Although we are now based in Australia, I continue to curate the website and update it as necessary with the help of friends and colleagues on the ground. If you click on Publications, then Articles, above, you will find a series of articles about our time in France, written for various newspapers over the 30 years of our association with the country.

Monpazier is considered to be the most perfect, and best preserved, of all the 300-plus bastides that have survived in the Aquitaine region, singled out by no less an authority than Le Corbusier. In 1991, it was declared 'un grand site national' - a national treasure. No surprise therefore that it attracts an estimated 250,000 visitors a year.

LATEST UPLOADS : Below is a list of the most recent items with key words in bold caps. To locate each, put a key word(s) in the SEARCH box (Command F), followed by two taps, or more, on the return key until the item appears. For the 'permanent core items' on the history of Monpazier and the bastides, scroll down...

LATEST UPLOADS : Below is a list of the most recent items with key words in bold caps. To locate each, put a key word(s) in the SEARCH box (Command F), followed by two taps, or more, on the return key until the item appears. For the 'permanent core items' on the history of Monpazier and the bastides, scroll down...

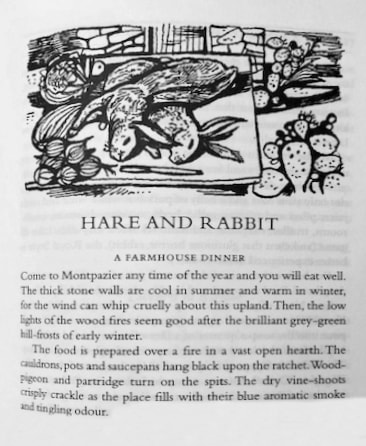

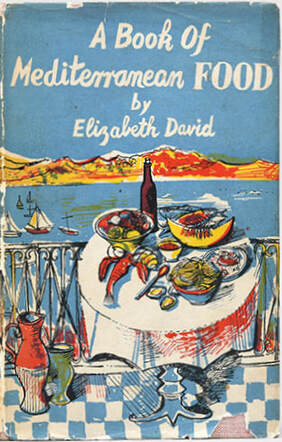

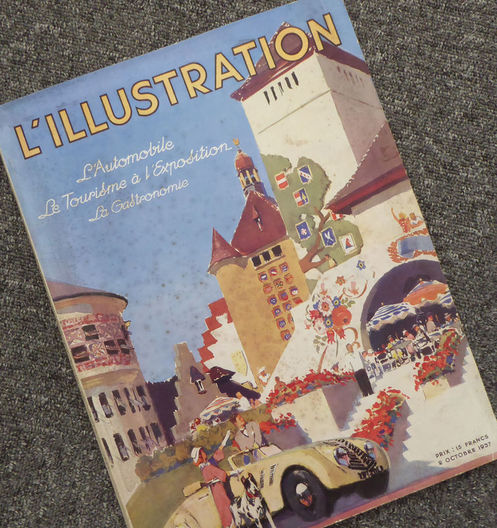

ELIZABETH DAVID'S VICARIOUS VISIT Did she - or didn't she? A culinary mystery story

L'ENTENTE CORDIALE IN A BOTTLE Why French soda was sold in English bottles

THE JUPITER JOINT How the Bordeaux boat-builders came inland

THE MANSARD ROOF François Mansard, the 'Monsieur Velux' of his day

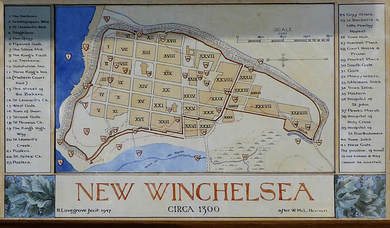

WINCHELSEA Monpazier's English sibling

WORTHY OF MONTY PYTHON A tale of 'reciprocal pillage'

THE MIRACULOUS 'BREAD TREE' How a tree saved whole families from starvation

THE CURSE OF CRENELATION What Viollet-le-Duc did - and fortunately did not do - for Monpazier

AVIAN VERMIN Why pigeons, rather than a nuisance, could be a 'living larder'

MEASURE FOR MEASURE The truth behind Monpazier's measuring bins

A WEEKEND OF MOYENAGERIE Monpazier's annual Fête Médiévale

L'ENTENTE CORDIALE IN A BOTTLE Why French soda was sold in English bottles

THE JUPITER JOINT How the Bordeaux boat-builders came inland

THE MANSARD ROOF François Mansard, the 'Monsieur Velux' of his day

WINCHELSEA Monpazier's English sibling

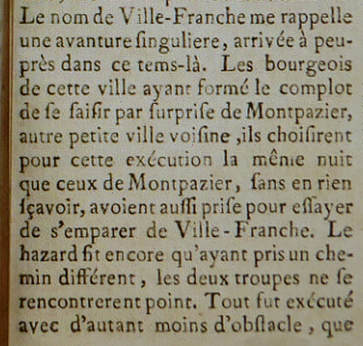

WORTHY OF MONTY PYTHON A tale of 'reciprocal pillage'

THE MIRACULOUS 'BREAD TREE' How a tree saved whole families from starvation

THE CURSE OF CRENELATION What Viollet-le-Duc did - and fortunately did not do - for Monpazier

AVIAN VERMIN Why pigeons, rather than a nuisance, could be a 'living larder'

MEASURE FOR MEASURE The truth behind Monpazier's measuring bins

A WEEKEND OF MOYENAGERIE Monpazier's annual Fête Médiévale

THE BIRTH OF THE BASTIDE

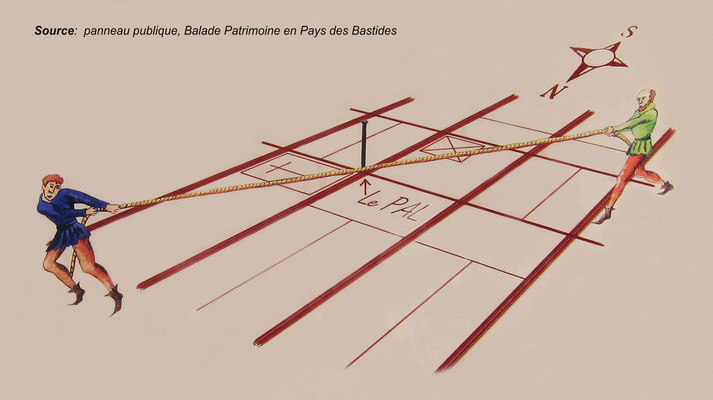

It’s the seventh day of January in the year 1284 – and probably vachement froid. A small group is gathered on a plateau of cleared land known as 'La Boursie'. It measures about 400 by 220 metres, falls away on three sides and overlooks the valley of the River Dropt. One of the group is holding a pole, bearing the arms of Edward 1st, King of England, and those of Pierre de Gontaut, the local Lord of Biron and Edward's business partner in the joint enterprise. The pole – ‘le Pal’ – is placed in the central hole of a stone block sunk into the ground by a team of surveyors (The hole can still be seen today just beyond the north-east corner of the central square. Photo left).

There is a short speech, read from a scroll of parchment. Here, it has been decreed, will be built a new town. It will be called Montis Pazerii – the Mount of Peace. Public criers with trumpets are despatched to the surrounding countryside to proclaim the birth of the bastide and recruit ‘candidats-habitants’ as its future citizens.

It’s the seventh day of January in the year 1284 – and probably vachement froid. A small group is gathered on a plateau of cleared land known as 'La Boursie'. It measures about 400 by 220 metres, falls away on three sides and overlooks the valley of the River Dropt. One of the group is holding a pole, bearing the arms of Edward 1st, King of England, and those of Pierre de Gontaut, the local Lord of Biron and Edward's business partner in the joint enterprise. The pole – ‘le Pal’ – is placed in the central hole of a stone block sunk into the ground by a team of surveyors (The hole can still be seen today just beyond the north-east corner of the central square. Photo left).

There is a short speech, read from a scroll of parchment. Here, it has been decreed, will be built a new town. It will be called Montis Pazerii – the Mount of Peace. Public criers with trumpets are despatched to the surrounding countryside to proclaim the birth of the bastide and recruit ‘candidats-habitants’ as its future citizens.

Shortly after the opening ceremony, surveyors attach ropes to the pole and measure out the rectangular grid upon which the buildings will be erected. Successful candidates for citizenship will have access to free wood and stone for one year to build their houses, and will have to take up residence within three. At its medieval height, Monpazier will have between 2000 and 2500 inhabitants – about four times its present population.

An aerial shot of Monpazier taken by my high-flying neighbour Andy Simpson in August 2017. It shows to advantage Monpazier's distinctive grid pattern and how the bastide manages to be both framed by the surrounding countryside and raised above it.

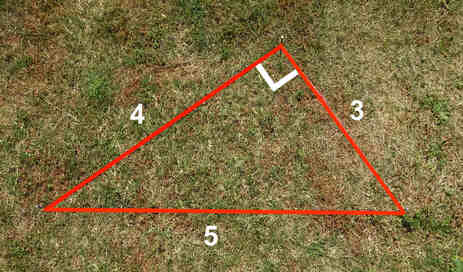

MEDIEVAL SURVEYORS - HOW DID THEY DO IT?

The future Monpazier was a reasonably flat ‘greenfield site’, but to fill the 400 x 220 metre rectangle would still have required the professional skills of surveyors (arpenteurs) to lay out the main square and all the surrounding building plots. A challenge indeed... particularly ensuring that the right-angles are 'right'. The theodolite wouldn't be invented until around 1500, while GPS wasn’t even dreamed of. But medieval surveyors had to hand a piece of equipment that couldn't have been more basic, yet which, according to some, was used by the Egyptians to build their pyramids: a loop of rope with twelve equally-spaced knots.

MEDIEVAL SURVEYORS - HOW DID THEY DO IT?

The future Monpazier was a reasonably flat ‘greenfield site’, but to fill the 400 x 220 metre rectangle would still have required the professional skills of surveyors (arpenteurs) to lay out the main square and all the surrounding building plots. A challenge indeed... particularly ensuring that the right-angles are 'right'. The theodolite wouldn't be invented until around 1500, while GPS wasn’t even dreamed of. But medieval surveyors had to hand a piece of equipment that couldn't have been more basic, yet which, according to some, was used by the Egyptians to build their pyramids: a loop of rope with twelve equally-spaced knots.

The 'trick' is to apply Pythagoras's theorem of the square on the hypotenuse...

So, using pegs, stretch taut the rope to measure out a triangle on the ground... make the number of spaces between the knots 3,4,5 units respectively... et voilà! You will have the perfect right-angle every time!

The Egyptians pre-dated the Greek Pythagoras by a couple of millennia, so either Pythagoras got his theorem from them or both he and the Egyptians hit on the idea independently. Whichever the source, it survived into the ‘dark’ Middle Ages.

So, using pegs, stretch taut the rope to measure out a triangle on the ground... make the number of spaces between the knots 3,4,5 units respectively... et voilà! You will have the perfect right-angle every time!

The Egyptians pre-dated the Greek Pythagoras by a couple of millennia, so either Pythagoras got his theorem from them or both he and the Egyptians hit on the idea independently. Whichever the source, it survived into the ‘dark’ Middle Ages.

NOT A BLOG: I’m suspicious of blogs. Too often they are licences for unsupported opinion, unstructured thought, sloppy writing (Hey, it’s only a blog!) or at worst a dire version of ‘WHAT I DID IN MY GAP YEAR’. If this were a blog, it would doubtless be titled, ‘A DUDE IN THE DORDOGNE’. So, if not a blog, what is it? Primarily it's observational. The best description I can come up with is: ‘an illustrated notebook with a journalistic edge’. But you're the judge...

THREE FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS...

How ‘English’ were the English kings of the Middle Ages?

Not very. Historians of the Middle Ages tend to talk about ‘Crowns’ – the English Crown and the French Crown – rather than England and France, or the English and the French. There’s a reason. William (the Conqueror), Duke of Normandy, crossed the Channel and invaded England in 1066. After victory at the Battle of Hastings, he was crowned King William Ist of England – and from then on for many decades so-called ‘English monarchs’ not only spoke French; they were French. A century later, the conflict between 'the English’ and ‘the French’ was more accurately between two branches of the French royal family: the Angevins (aka Plantagenets) based in England and the Capetians based in France.

As the historian Simon Schama has pointed out, the Magna Carta was signed by French barons... and that was in 1215.

How did the English Crown come to acquire a third of France in the form of Aquitaine?

Pretty well by chance – and a salutary example of the Law of Unintended Consequences...

Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine (inherited from her father), was originally married to the French (Capetian) king, Louis VII. The marriage was annulled after she had failed to bear him a male heir - or he had failed to provide the necessary means. He kept their daughters and, critically for what happened next, she kept her lands.

Just two months later Eleanor re-married – this time a member of the rival branch of the family, the Angevin Henry Plantagenet who had inherited the titles Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy. Through the dowry that Eleanor brought to the marriage, Henry now also became Duke of Aquitaine.

All of this would have remained an internal French affair, a mere re-allocation of national real estate – but for the fact that two years later in 1154 Henry added one more title to his collection: Henry II, King of England. The effect was seismic: Aquitaine now belonged to the English Crown… and would remain so for three hundred years.

* It's worth noting that Eleanor is the only woman to have been, by successive marriages, both Queen of France and Queen of England. Equally noteworthy in the context of her annulled first marriage is that, through her second marriage, she produced two future kings of England: John and Richard (the Lionhearted).

How ‘English’ were the English kings of the Middle Ages?

Not very. Historians of the Middle Ages tend to talk about ‘Crowns’ – the English Crown and the French Crown – rather than England and France, or the English and the French. There’s a reason. William (the Conqueror), Duke of Normandy, crossed the Channel and invaded England in 1066. After victory at the Battle of Hastings, he was crowned King William Ist of England – and from then on for many decades so-called ‘English monarchs’ not only spoke French; they were French. A century later, the conflict between 'the English’ and ‘the French’ was more accurately between two branches of the French royal family: the Angevins (aka Plantagenets) based in England and the Capetians based in France.

As the historian Simon Schama has pointed out, the Magna Carta was signed by French barons... and that was in 1215.

How did the English Crown come to acquire a third of France in the form of Aquitaine?

Pretty well by chance – and a salutary example of the Law of Unintended Consequences...

Eleanor, Duchess of Aquitaine (inherited from her father), was originally married to the French (Capetian) king, Louis VII. The marriage was annulled after she had failed to bear him a male heir - or he had failed to provide the necessary means. He kept their daughters and, critically for what happened next, she kept her lands.

Just two months later Eleanor re-married – this time a member of the rival branch of the family, the Angevin Henry Plantagenet who had inherited the titles Count of Anjou and Duke of Normandy. Through the dowry that Eleanor brought to the marriage, Henry now also became Duke of Aquitaine.

All of this would have remained an internal French affair, a mere re-allocation of national real estate – but for the fact that two years later in 1154 Henry added one more title to his collection: Henry II, King of England. The effect was seismic: Aquitaine now belonged to the English Crown… and would remain so for three hundred years.

* It's worth noting that Eleanor is the only woman to have been, by successive marriages, both Queen of France and Queen of England. Equally noteworthy in the context of her annulled first marriage is that, through her second marriage, she produced two future kings of England: John and Richard (the Lionhearted).

Portrait believed to be Edward I

Westminster Abbey

Portrait believed to be Edward I

Westminster Abbey

Where do the bastides and Monpazier feature in all this?

By the time Henry II’s great-grandson, Edward Ist, comes to the throne in 1272, more than two centuries have passed since the Norman Conquest. Edward, born in London, named after an Anglo-Saxon monarch-saint and taught English as a child, is not just ‘a Frenchy who happened to be King of England’ but an indisputably English monarch. By the same token, Aquitaine doesn't just ‘belong to the English Crown’, it is now seen – at least from the English side of the Channel – as part of England. (In much the same way as, centuries later, France would regard Algeria not as a colony but as part of France 'across the water'.)

By the time Henry II’s great-grandson, Edward Ist, comes to the throne in 1272, more than two centuries have passed since the Norman Conquest. Edward, born in London, named after an Anglo-Saxon monarch-saint and taught English as a child, is not just ‘a Frenchy who happened to be King of England’ but an indisputably English monarch. By the same token, Aquitaine doesn't just ‘belong to the English Crown’, it is now seen – at least from the English side of the Channel – as part of England. (In much the same way as, centuries later, France would regard Algeria not as a colony but as part of France 'across the water'.)

Edward pays homage - Jean Fouquet, 'Les Rois de France'

Bibliotèque Nationale, Paris

Edward pays homage - Jean Fouquet, 'Les Rois de France'

Bibliotèque Nationale, Paris

Towards the end of the 1200’s, tension and taunting between the two sides ramp up. Edward, though a monarch in his own right, is still expected, as Duke of Aquitaine, to pay homage to the King of France, Philip IV, in whose kingdom his territory lies. It’s a knee-bending formality but one which irks the English Crown and will ultimately lead to the Hundred Years War. In anticipation of conflict, each side stakes out its territory.

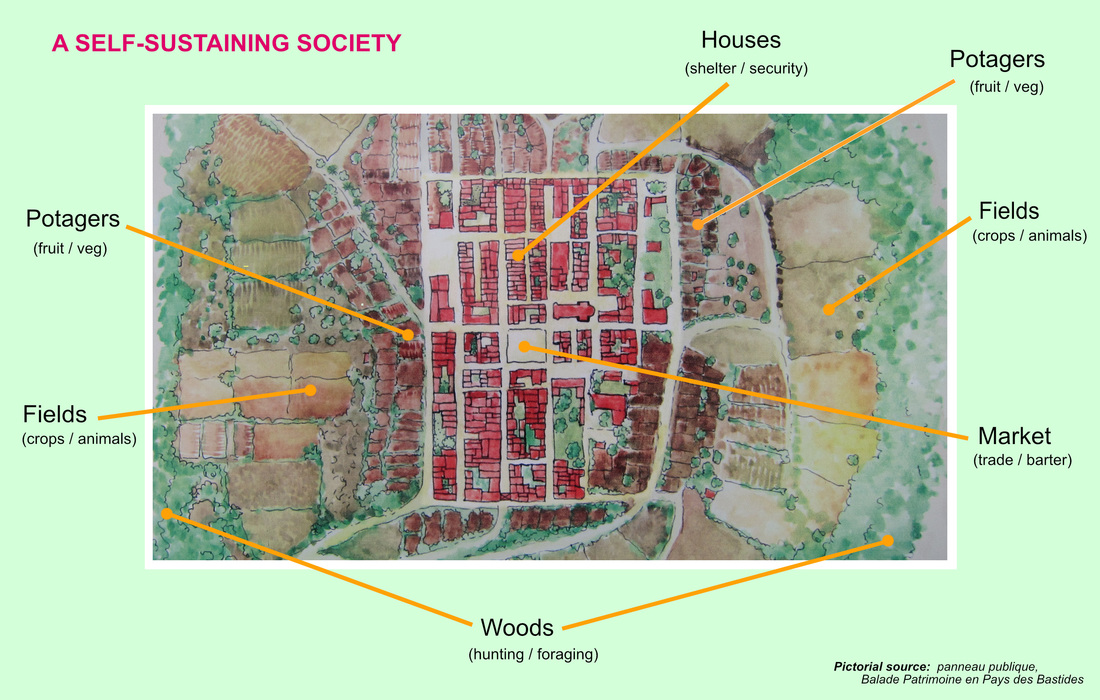

Initially, the chosen strategy is commerce rather than combat. Both sides realise the value of planting settlements – creating ‘facts on the ground’ - along the boundaries of their respective territories. But to function and, no less, to be defended, these require human inhabitants. So the bastides are born – designated centres of trade with regular weekly markets and fairs which will attract permanent residents from the surrounding area by offering shelter, protection and self-sufficiency… even the pursuit of prosperity.

The upper reaches of the River Dropt become the focal point of the confrontation. It’s a face-off. On the south bank, Alphonse de Poitiers, the French king’s brother, establishes the bastides of Eymet, Castillonnès, Villeréal and Villefranche-du-Périgord. North of the river, the English King Edward orders the construction of Molières, Beaumont… and in 1284, Monpazier*.

* The first of the English bastides, Lalinde, had already been founded by Edward in 1267 when he was still Prince Edward.

Initially, the chosen strategy is commerce rather than combat. Both sides realise the value of planting settlements – creating ‘facts on the ground’ - along the boundaries of their respective territories. But to function and, no less, to be defended, these require human inhabitants. So the bastides are born – designated centres of trade with regular weekly markets and fairs which will attract permanent residents from the surrounding area by offering shelter, protection and self-sufficiency… even the pursuit of prosperity.

The upper reaches of the River Dropt become the focal point of the confrontation. It’s a face-off. On the south bank, Alphonse de Poitiers, the French king’s brother, establishes the bastides of Eymet, Castillonnès, Villeréal and Villefranche-du-Périgord. North of the river, the English King Edward orders the construction of Molières, Beaumont… and in 1284, Monpazier*.

* The first of the English bastides, Lalinde, had already been founded by Edward in 1267 when he was still Prince Edward.

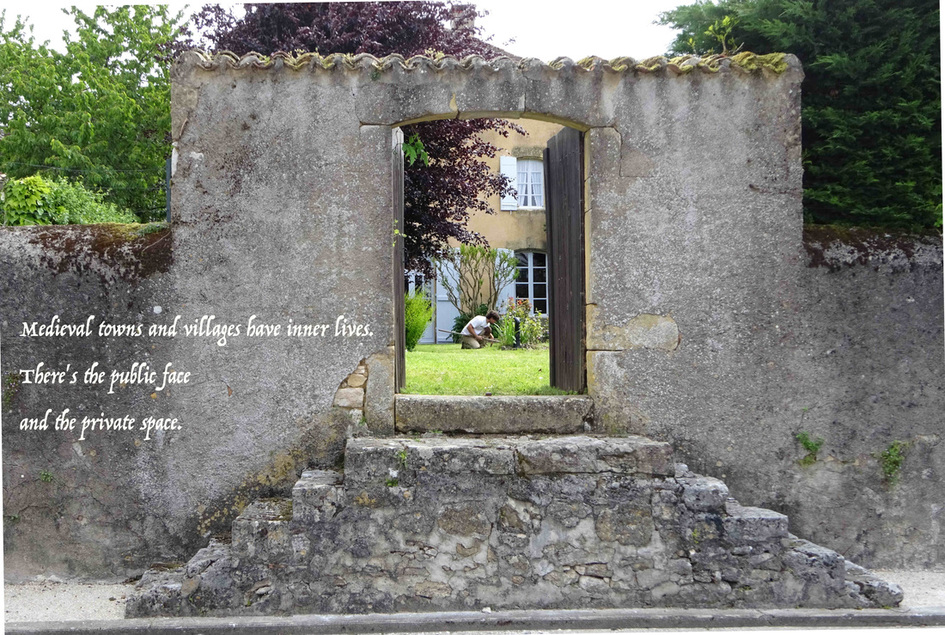

The medieval Monpazier was in many ways the perfect economic model: the town literally fed off the surrounding countryside.

If you were a peasant trying to live independently on the land or, more likely, the tied-serf of a local baron, there were obvious attractions in becoming a citizen of a bastide such as Monpazier. Not only were you allocated a plot within the town to build your own house, but – as part of the package - you also had a ‘potager’ ( an allotment-sized patch of land beneath the walls to grow fruit and veg), access to a field to cultivate crops or raise livestock... and, not least, the right to go hunting small game and foraging in the woods beyond. On top of all that, any surplus to your and your family's needs could be sold or bartered in the market, held every week in the central square.

Fast forward seven hundred years to the Monpazier of the twenty-first century...

If you were a peasant trying to live independently on the land or, more likely, the tied-serf of a local baron, there were obvious attractions in becoming a citizen of a bastide such as Monpazier. Not only were you allocated a plot within the town to build your own house, but – as part of the package - you also had a ‘potager’ ( an allotment-sized patch of land beneath the walls to grow fruit and veg), access to a field to cultivate crops or raise livestock... and, not least, the right to go hunting small game and foraging in the woods beyond. On top of all that, any surplus to your and your family's needs could be sold or bartered in the market, held every week in the central square.

Fast forward seven hundred years to the Monpazier of the twenty-first century...

This 'aerial visualisation' is the work of the late Keith Godard, a British-born, Brooklyn-based, graphic designer. Keith, who died in May 2020, had a holiday home a few kilometres away in neighbouring Belvès. What makes the map unusual is that Keith applied not the rules of classical perspective (as taught at art schools) but 'isometric projection' - a way of seeing the world favoured by architects. The effect, when combined with Keith's subtle combinations of watercolour, is of a startlingly alternative reality that makes an aerial photograph look flat by comparison.

Photo: Keith in front of the halle, Belvès, 2016

Lithographs of the Keith Godard's three-dimensional map, measuring 70 cm x 50 cm, are available from Monpazier's interpretative centre BASTIDEUM or can be ordered direct from his widow, the architect Katrin Adam : [email protected]

Photo: Keith in front of the halle, Belvès, 2016

Lithographs of the Keith Godard's three-dimensional map, measuring 70 cm x 50 cm, are available from Monpazier's interpretative centre BASTIDEUM or can be ordered direct from his widow, the architect Katrin Adam : [email protected]

MEASURE FOR MEASURE

(or 'The Bins of Mystery')

Measuring bins were essential for the efficient function of a medieval market – first to guarantee the buyer the correct amount (corn, wheat, barley, chestnuts, etc.) and second, no less important, to enable the authorities to collect the appropriate tax at the point of sale. These are Monpazier's bins in the main square. They were filled up from the top, tilted, and their contents were poured via the small ‘gate’ into sacks below. You’ll find bins like these in other bastides, both English and French (e.g. Monflanquin) – but Monpazier’s bins have their own story to tell…

(or 'The Bins of Mystery')

Measuring bins were essential for the efficient function of a medieval market – first to guarantee the buyer the correct amount (corn, wheat, barley, chestnuts, etc.) and second, no less important, to enable the authorities to collect the appropriate tax at the point of sale. These are Monpazier's bins in the main square. They were filled up from the top, tilted, and their contents were poured via the small ‘gate’ into sacks below. You’ll find bins like these in other bastides, both English and French (e.g. Monflanquin) – but Monpazier’s bins have their own story to tell…

Guide books often refer to the bins as being ‘original’. Well, highly unlikely, given that they are made of iron and out in the open all seasons. Over the course of seven centuries, they will have been regularly repaired and replaced. But it was always assumed that the replacements would at least have been exact copies of the originals… until, a few years ago, someone interested in medieval weights and measures decided to check just how much they would have contained. To their surprise, it turned out that the bins had been ‘metricized’. Since metrication was introduced during the French Revolution, the present bins must date from the 1790s at the earliest. This is unlikely to have been a purely ornamental change, so one can reasonably infer that they would also have been in regular use. For the record, the largest bin has an internal diameter of 50 centimetres and is 50 centimetres deep – which means, when filled to the brim, it would take one-tenth of a cubic metre. A manageable sack-full.

A WEEKEND OF

MOYENAGERIE

There’s a well-worn story about an epic Hollywood movie of the 1950s in which, before the set-piece battle, the hero exhorts his troops with the words: Men of the Middle Ages, you are about to embark on The Hundred Years War!

Today's Monpazier - not needing the benefit of such prescience - has its own version of The Hundred Years War, albeit somewhat scaled down. It is the annual Fête Médiévale, usually held at the height of the tourist season in late July. Participants come from all around to swing swords and wag wimples. In 2019, my colleague Clint Dougherty (ex-Hollywood cameraman) and I were persuaded by the mayor to capture the event on video. It’s on YouTube at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aAUJI9moy_U&feature=share&fbclid=IwAR3dXXmnnM-j4kdYmiQumj8PBdzSR_HCucRJQQwgA1RtEexL48d1OI2Sow8

The Fête's historical authenticity is occasionally a touch ‘impressionistic’ – with the English King Edward 1st wearing French Bourbon blue – but condensing a hundred years into two days inevitably involves some licence and compromise…

Technical note: We decided to shoot the video not with conventional cameras but with smart-phones mounted on gimbals. Initially sceptical, I ended up being totally won over. Judge for yourself and, if you can't tell the difference, make a token contribution to the Redundant Cameramens' Benevolent Fund...

Technical note: We decided to shoot the video not with conventional cameras but with smart-phones mounted on gimbals. Initially sceptical, I ended up being totally won over. Judge for yourself and, if you can't tell the difference, make a token contribution to the Redundant Cameramens' Benevolent Fund...

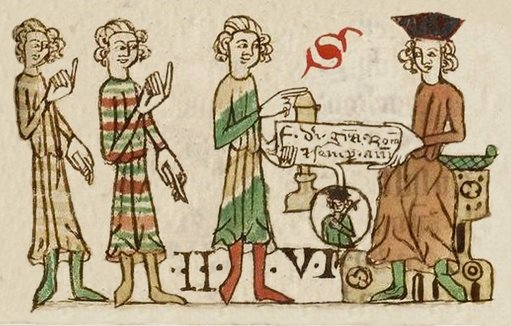

Detail from Heidelberger Sachsenspiegel;

Heidelberg University Library

Detail from Heidelberger Sachsenspiegel;

Heidelberg University Library

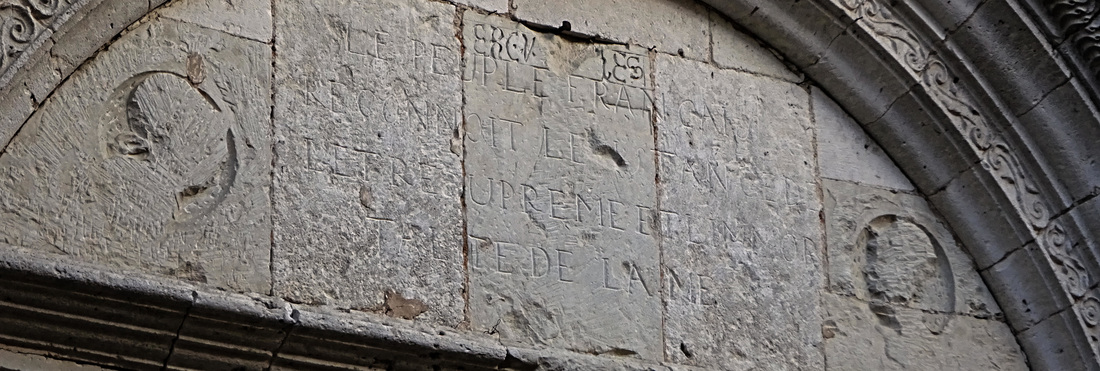

THE CHARTER OF CUSTOMS

Establishing a bastide was about more than laying out the plan and building the houses. As an added incentive, the founding Seigneurs also offered potential citizens a Charte de Coutumes, literally, a Charter of Customs.

This was in effect a local constitution – a mix of citizens’ rights, penal code and fiscal regulations. Equally, it can be seen as an early form of Social Contract: ‘If you, the citizens, agree to observe the laws and pay your taxes… we, your rulers, will protect you, your family and your possessions and guarantee you certain specified liberties’.

Above: Citizens receiving charter show their digital delight

Establishing a bastide was about more than laying out the plan and building the houses. As an added incentive, the founding Seigneurs also offered potential citizens a Charte de Coutumes, literally, a Charter of Customs.

This was in effect a local constitution – a mix of citizens’ rights, penal code and fiscal regulations. Equally, it can be seen as an early form of Social Contract: ‘If you, the citizens, agree to observe the laws and pay your taxes… we, your rulers, will protect you, your family and your possessions and guarantee you certain specified liberties’.

Above: Citizens receiving charter show their digital delight

Although remarkable for its time, the Charter was subtly skewed in favour of the Seigneur. This was no philanthropic exercise. Yes, it offered a host of individual liberties but it also restricted the collective ones.

Unfortunately, the charter for Monpazier has been lost (not down the back of the mayor’s sofa after the last election party but several centuries ago). The charters of other bastides that have survived, though, suggest they were all very similar. Since we still have those for three neighbouring bastides - the English Lalinde and Beaumont, and the French Monflanquin – we have a good idea of what would have been in the Monpazier charter. It's telling that, although the French and English bastides were ‘in opposition’, the English rulers had no scruples about cribbing the existing French charters pretty well line for line.

Unfortunately, the charter for Monpazier has been lost (not down the back of the mayor’s sofa after the last election party but several centuries ago). The charters of other bastides that have survived, though, suggest they were all very similar. Since we still have those for three neighbouring bastides - the English Lalinde and Beaumont, and the French Monflanquin – we have a good idea of what would have been in the Monpazier charter. It's telling that, although the French and English bastides were ‘in opposition’, the English rulers had no scruples about cribbing the existing French charters pretty well line for line.

Among the thirty or more articles, the main points:

* No inhabitant can be arrested, harmed or have his property seized except in cases of murder, inflicting injury or other

crimes. (Compare this with Clause 39 of England's Magna Carta, 1215: " No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped

of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any way, nor will we proceed with force against

him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.")

* Inhabitants have the right to own property, can dispose of it however they choose and sell it to whomever

they wish without the consent of the Seigneur. This includes the bequeathing of property and goods to their heirs.

* Inhabitants can marry off their daughters to whom they wish – again without needing the consent of the Seigneur.

* Inhabitants are required to pay rent for their houses and land, and to contribute to the general upkeep of the

bastide - i.e. pay ‘rates’. (They would also be expected to pay a tithe, a percentage of their income, to the Church).

* No inhabitant can be arrested, harmed or have his property seized except in cases of murder, inflicting injury or other

crimes. (Compare this with Clause 39 of England's Magna Carta, 1215: " No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped

of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any way, nor will we proceed with force against

him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.")

* Inhabitants have the right to own property, can dispose of it however they choose and sell it to whomever

they wish without the consent of the Seigneur. This includes the bequeathing of property and goods to their heirs.

* Inhabitants can marry off their daughters to whom they wish – again without needing the consent of the Seigneur.

* Inhabitants are required to pay rent for their houses and land, and to contribute to the general upkeep of the

bastide - i.e. pay ‘rates’. (They would also be expected to pay a tithe, a percentage of their income, to the Church).

And there was a form of self-government... The Bayle, as representative of the Seigneur, would be the titular ruler - a sort of Mayor. But, beneath him, there would typically be half a dozen Consuls - the equivalent of today’s town councillors - who would act as ‘representatives of the people’ in administering the day-to-day activity of the bastide. And the Charter required that they be regularly rotated:

* The Consuls will be changed every year. They will be chosen initially by the Seigneur or his representative, the Bayle, and

thereafter the outgoing Consuls will choose the next incumbents of the posts - the selection to be made from those

inhabitants judged to be the most honest and most useful to the community. (Some historians have talked of Consuls being

'elected'. This is misleading. You could, at a pinch, argue that the process is a form of self-government but it's a far cry

from the 'one man, one vote' representative democracy we know today. At worst, it has all the potential to be a self-

perpetuating Club des Vieux Garçons.)

* The Consuls will receive no recompense for their official duties.

* The Consuls will be changed every year. They will be chosen initially by the Seigneur or his representative, the Bayle, and

thereafter the outgoing Consuls will choose the next incumbents of the posts - the selection to be made from those

inhabitants judged to be the most honest and most useful to the community. (Some historians have talked of Consuls being

'elected'. This is misleading. You could, at a pinch, argue that the process is a form of self-government but it's a far cry

from the 'one man, one vote' representative democracy we know today. At worst, it has all the potential to be a self-

perpetuating Club des Vieux Garçons.)

* The Consuls will receive no recompense for their official duties.

One other key article would have regulated the most important function of the bastide: commerce - the buying and selling of goods. For inhabitants this would have been their biggest source of income and potential prosperity:

* The weekly market will be held on Thursday. Outsiders have to pay a fee to sell their produce or merchandise but inhabitants

of Monpazier are exempt. The same will apply to fairs. (Whether or not specifically mentioned in the Charter, all buying and

selling would have to take place in the main square to prevent illegal, tax-dodging side deals being done in back streets.)

* The weekly market will be held on Thursday. Outsiders have to pay a fee to sell their produce or merchandise but inhabitants

of Monpazier are exempt. The same will apply to fairs. (Whether or not specifically mentioned in the Charter, all buying and

selling would have to take place in the main square to prevent illegal, tax-dodging side deals being done in back streets.)

Finally, law and order – and certainly no lack of specifics here:

* Anyone who viciously hits or maltreats an inhabitant with the fist, the hand or the foot but without drawing blood will, in the

event of a complaint, have to pay five sols (don’t ask) to make good the assault.

* If the blow is with a sword, a stick, a stone or a tile – but again without drawing blood – the fine will be twenty sols.

* If blood is shed, the guilty person will have to pay sixty sols and additionally compensate the victim.

* Anyone who viciously hits or maltreats an inhabitant with the fist, the hand or the foot but without drawing blood will, in the

event of a complaint, have to pay five sols (don’t ask) to make good the assault.

* If the blow is with a sword, a stick, a stone or a tile – but again without drawing blood – the fine will be twenty sols.

* If blood is shed, the guilty person will have to pay sixty sols and additionally compensate the victim.

Oh, and not forgetting theft and adultery...

* Depending on the seriousness of the offence, thieves will suffer a range of punishments from a fine to hanging. They may also

be required to run across town with the stolen object hanging around their neck.

* Those engaged in adultery will be liable to the stiffest fine of all: 100 sols each. As an alternative punishment, to add to the

jollity of the local population, they may choose to run across town... naked.

* Depending on the seriousness of the offence, thieves will suffer a range of punishments from a fine to hanging. They may also

be required to run across town with the stolen object hanging around their neck.

* Those engaged in adultery will be liable to the stiffest fine of all: 100 sols each. As an alternative punishment, to add to the

jollity of the local population, they may choose to run across town... naked.

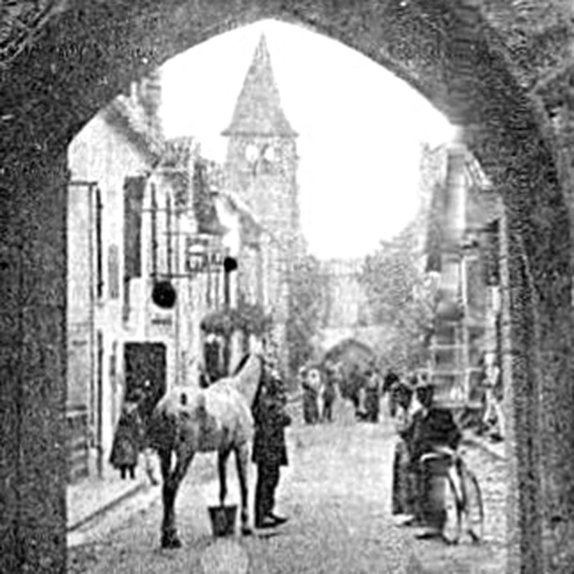

The Church of St Dominique framed in one of the arches of La Place des Cornières. Typically in a medieval European town the church would be the central building and dominate the main square. Not here. One of the most telling features of many of Aquitaine's bastides is that the church, though built close to the square, is not actually in it (See Keith Godard's map above). Commerce, not worship, was the raison d'être of the bastide; first and foremost, it was a place where locals and outsiders could meet in a designated spot to buy and sell. God had His place but, geographically, it wasn't central to the daily life of the community. You see the same pattern in the neighbouring bastides of Villeréal, Monflanquin, Beaumont-du-Périgord and Sauveterre de Guyenne - all with their churches just beyond the main square. That said, we don't know the reason. Was God being made subservient to Mammon... or was He tactfully being spared the sight, and sound, of the money-changers?

Another view of Saint-Dominque - seen from the south-west corner of the village, rising above the rooftops. The church was one of the first structures to be build following foundation in 1284 - not just as a place of worship but, no less important, as a fortified haven in the event of attack. Building continued into the 16th century. And yes, the roof of the bell-tower really is inclined at a jaunty angle, though the Commune hasn't yet hit upon The Tilting Tower of Monpazier as tourist bait. Off to the far left is the Maison du Chapitre, the second highest structure within the walls.

A bright, crisp January morning. The temperature is in single figures but the sun is shining and the sky is blue. This is the best time to appreciate Monpazier's unique architectural diversity, uncluttered by human activity. What makes La Place des Cornières exceptional is the sense of unity in diversity. If you stand in the centre of the square and slowly turn through 360 degrees, you are presented on all four sides with buildings of different styles and eras, from at least the thirteen hundreds up to the seventeen hundreds - buildings which moreover have been frequently repaired and renovated over the centuries, and continue to be so. And yet, for all that each building is a 'soloist' in its own right, the collective atmosphere is one of perfect harmony. If ever there were an essential lesson for budding architects, this has to be it.

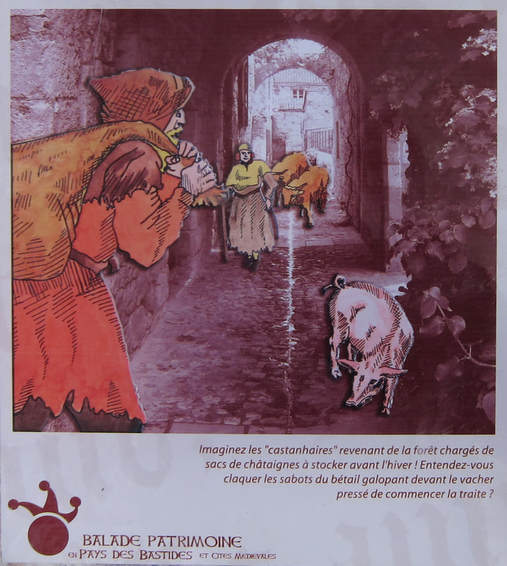

THE MIRACULOUS ‘BREAD TREE’

These days we tend to take trees for granted. Cords of wood stacked by the roadside typically prompt the thought, ‘They’d burn well in the Jøtel’. But for our medieval forebears trees were an invaluable resource in countless different ways – and not just fruit trees. Oaks offered sturdy, rot-resistant timber for both houses and boats, not forgetting acorns for the pigs; domestic furniture was made from elm; poplars drained boggy land; walnuts were pressed for their oil. But for those living in the Périgord nothing beat the sweet chestnut. It too could be used for timbers (Monpazier’s halle is made of it) but the nuts themselves were no less prized because they could be turned into a highly nutritious flour - and baked. Rich in minerals, vitamins and phytonutrients, they were a winter life-saver if the crops had failed. Hence the sweet chestnut came to be known as ‘The Bread Tree’.

For the ‘castanhaires’ - the Occitan word for the chestnut-gatherers – October was the busiest month. Right is one of Monpazier's fifteen 'interpretive' panels erected around the village for the benefit of visitors. This one depicts one of Monpazier's carreyrou alleyways.

Panneau publique, Balade Patrimoine en Pays des Bastides

Panneau publique, Balade Patrimoine en Pays des Bastides

The north gates - both of them. Originally, Monpazier is thought to have had six gates: two north, two south, one east, one west. Three have survived: the two north and one south. Bastides are often described as 'fortified' towns or villages - the implication being that, from the laying of the first stone, they were conceived and planned with walls, ditches and ramparts. This may be the result of a confused belief that the word 'bastide' was related to 'bastille', meaning a fortress (and, subsequently, a prison). But there is now an academic consensus that in many cases this was not the case. A number of Aquitaine's bastides - Monpazier included - started out as 'open' communities to promote commerce. Yes, they would have had gates - but these (and the curfews that went with them) were primarily to keep out criminal riff-raff rather than enemy troops bent on regime-change. Actual fortifications - high, thick defensive walls between the gates - came only some decades later during the run-up to The Hundred Years War when the first hostilities broke out between the French and English crowns. A curious feature of Monpazier is that, instead of seriously defensive walls on the northern front - the most vulnerable side - there are only in-fill houses. Did these replace earlier walls or did the Monpaziérois feel that, despite the multiple openings of doors and windows, they would 'do the job'?

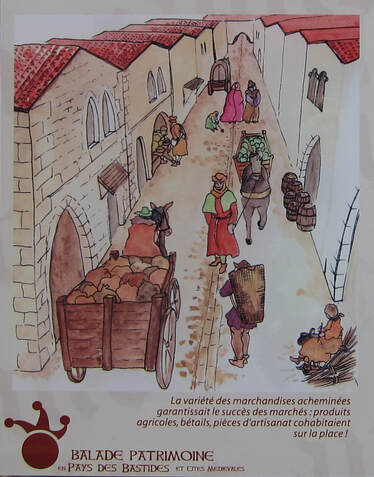

RULES OF THE ROAD

Another of Monpazier's ‘interpretive’ panels... This one shows how the exceptional width – eight metres - of the bastide's two principal roads enabled carts to pass each other and so avoid congestion on market days.

Something odd about it? Even plain wrong?

The carters are driving on the left – when, as we all know, the French drive on the right. But in fact the depiction is historically correct. The French, like the British, used to drive on the left. They switched to the right only after the Revolution of 1789.

The practice of keeping to the left is generally explained by the greater ease of drawing one’s sword (assuming one is right-handed) in a single movement if approached by a stranger with less-than-friendly intentions. Well, possibly. Arguably a more plausible reason is that horses, the precursors of the automobile, have always been mounted from the left side – the near side of the track, street or highway. Why? Perhaps because it’s more natural for the right-handed majority of riders. Or maybe it’s something to do with the way horses’ brains are configured that they prefer it that way. (Any animal psychologists out there?)

As to why the French made the switch to the right after the Revolution, it seems to have been symbolic. Mindful of their personal safety, the aristocracy of the ancien régime would keep left when passing those of the lower orders (again, the self-defence consideration). But once the Revolution had effectively abolished the aristocracy, everyone was in theory a ‘citizen’ and so identifying with the peasants on the right was politically correct and, in terms of self-preservation, a smart move. Napoleon, a product of the Revolution, duly put it into law - not just in his own country but also in those he conquered (e.g. Egypt).

Another of Monpazier's ‘interpretive’ panels... This one shows how the exceptional width – eight metres - of the bastide's two principal roads enabled carts to pass each other and so avoid congestion on market days.

Something odd about it? Even plain wrong?

The carters are driving on the left – when, as we all know, the French drive on the right. But in fact the depiction is historically correct. The French, like the British, used to drive on the left. They switched to the right only after the Revolution of 1789.

The practice of keeping to the left is generally explained by the greater ease of drawing one’s sword (assuming one is right-handed) in a single movement if approached by a stranger with less-than-friendly intentions. Well, possibly. Arguably a more plausible reason is that horses, the precursors of the automobile, have always been mounted from the left side – the near side of the track, street or highway. Why? Perhaps because it’s more natural for the right-handed majority of riders. Or maybe it’s something to do with the way horses’ brains are configured that they prefer it that way. (Any animal psychologists out there?)

As to why the French made the switch to the right after the Revolution, it seems to have been symbolic. Mindful of their personal safety, the aristocracy of the ancien régime would keep left when passing those of the lower orders (again, the self-defence consideration). But once the Revolution had effectively abolished the aristocracy, everyone was in theory a ‘citizen’ and so identifying with the peasants on the right was politically correct and, in terms of self-preservation, a smart move. Napoleon, a product of the Revolution, duly put it into law - not just in his own country but also in those he conquered (e.g. Egypt).

Quintessential Monpazier en saison. It's high summer... artists sketching under the Halle... tourists relaxing outside L'Écureuil café... and a local on her bicycle going about her petit train-train. It's all there.

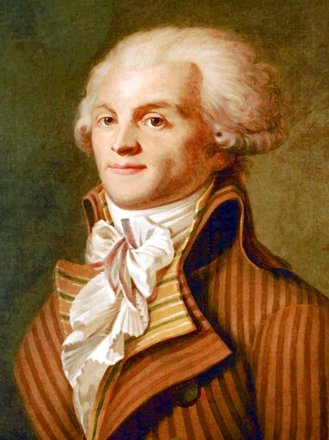

EDWARD 1st WAS HERE

As Duke of Aquitaine, Edward was no stranger to the region. In all he made five visits – both as Prince Edward when his father Henry III was on the throne and later after he himself became king in 1272. His longest visit lasted three years and three months - from 1286 to 1289 - and took in Monpazier.

Edward arrived in Monpazier, with his court, on 6th November 1286 - and wasn’t best pleased. Like the modern-day homeowner who leaves the builders to get on with the new conservatory and returns to discover they haven’t even poured the slab, Edward found a lot of marked-out plots with nothing on them. It was explained to him – one imagines with some trepidation – that, although a goodly number of ‘candidate-inhabitants’ had been accepted and assigned their plots, they hadn’t actually got round to building the houses.

Whether His Majesty threw a right-royal wobbly is not recorded but it’s probably indicative of his mood that he threatened the tardy inhabitants with a hefty fine if they didn’t get on with it. Since there’s no mention of the fine ever being levied, it seems to have had the desired effect.

How long Edward stayed in Monpazier we don’t know but his next stop – a day’s journey away – was Monflanquin (founded by the French but now under English control) where on 12th November he was busy signing ‘letters patent’. So, given that he arrived in Monpazier on the 6th, his timetable would have allowed him to stay two or three days before moving on.

As Duke of Aquitaine, Edward was no stranger to the region. In all he made five visits – both as Prince Edward when his father Henry III was on the throne and later after he himself became king in 1272. His longest visit lasted three years and three months - from 1286 to 1289 - and took in Monpazier.

Edward arrived in Monpazier, with his court, on 6th November 1286 - and wasn’t best pleased. Like the modern-day homeowner who leaves the builders to get on with the new conservatory and returns to discover they haven’t even poured the slab, Edward found a lot of marked-out plots with nothing on them. It was explained to him – one imagines with some trepidation – that, although a goodly number of ‘candidate-inhabitants’ had been accepted and assigned their plots, they hadn’t actually got round to building the houses.

Whether His Majesty threw a right-royal wobbly is not recorded but it’s probably indicative of his mood that he threatened the tardy inhabitants with a hefty fine if they didn’t get on with it. Since there’s no mention of the fine ever being levied, it seems to have had the desired effect.

How long Edward stayed in Monpazier we don’t know but his next stop – a day’s journey away – was Monflanquin (founded by the French but now under English control) where on 12th November he was busy signing ‘letters patent’. So, given that he arrived in Monpazier on the 6th, his timetable would have allowed him to stay two or three days before moving on.

The essential fact is that Edward was here – living, breathing, eating, drinking… and, as was his habit, assiduously inspecting everything. Today's visitors crossing La Place des Cornières would have to be singularly impervious to the pull of history not to feel a certain frisson - the realization that they are walking, literally, in the footsteps of one of England’s truly great warrior-monarchs: Edward Longshanks, subjugator of Wales, conqueror of Scotland, indefatigable founder of bastides and builder of castles , a man feared and respected across Europe in equal measure.

In the words of one chronicler, ‘a great and terrible king’.

Left: Edward's triple-lion Plantagenet flag still flying over the village

In the words of one chronicler, ‘a great and terrible king’.

Left: Edward's triple-lion Plantagenet flag still flying over the village

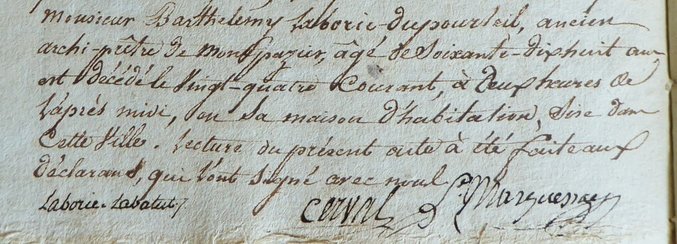

DISCLAIMER ALERT! I know, I know… Having lured you into this webpage with the promise of revelation and even titilation, here I am now burying a disclaimer several pages in… Just a reminder that, despite the slick veneer of erudition, I am not an historian or an academic of any sort. I am a TV journalist and producer. That said, even pukka historians will admit that there is always a problem when writing about medieval places because of the scarcity of primary sources. This is compounded in France by the disruption of the Hundred Years War, the Wars of Religion and, not least, The Revolution – when so many records were removed, misplaced or destroyed.

To give an example… Back in the 1990s, I was asked to write an English guide for a village we then lived in, just over the border in the Lot-et-Garonne. I consulted a couple of ‘local historians’ and found they disagreed on almost every essential fact. So I went to the Mairie (Town Hall) and asked to see their archives relating to medieval times. ‘Ah, Monsieur,’ they responded with ill-concealed glee, ‘your English ancestors took them away at the end of the Hundred Years War – so they will now be in the Tower of London’. Very fanciful, you may think. As did I. But it turned out there was more than a grain of truth in the assertion.

After the English defeat at the Battle of Castillon in 1453, the losers did indeed take wagonloads of written material with them back to England and, yes, it was originally stored in the Tower of London. Subsequently these ‘rolls’, as they are called, were moved to the Public Record Office – where they are today and available for inspection on application. I duly followed the trail to the PRO at Kew, just outside London, but it very soon became clear that there was only the slightest chance of the rolls for our particular village having ended up back in England, and to have employed the services of a professional researcher capable of deciphering the stacks and stacks of material would have cost more than the Mairie was willing even to consider. It was far more likely that any records had been lost or destroyed during the Revolution – but, from the French perspective, it was much more satisfying of course to blame the perfidious English.

After the English defeat at the Battle of Castillon in 1453, the losers did indeed take wagonloads of written material with them back to England and, yes, it was originally stored in the Tower of London. Subsequently these ‘rolls’, as they are called, were moved to the Public Record Office – where they are today and available for inspection on application. I duly followed the trail to the PRO at Kew, just outside London, but it very soon became clear that there was only the slightest chance of the rolls for our particular village having ended up back in England, and to have employed the services of a professional researcher capable of deciphering the stacks and stacks of material would have cost more than the Mairie was willing even to consider. It was far more likely that any records had been lost or destroyed during the Revolution – but, from the French perspective, it was much more satisfying of course to blame the perfidious English.

The bottom line is that very often, in the absence of archival evidence, one has to rely upon ‘local knowledge’, however inconsistent and unreliable, even when relating to events within current lifespans. In such situations, one can only resort to weasel words like ‘estimated’, ‘consensus’ and ‘generally agreed’ - or just admit that nobody really knows.

A single tower remains on the eastern side of the village. Beneath it, a 'medieval' garden, stocked with medicinal herbs. To visit it, you must walk from the Place des Cornières, down to the bottom of the rue Galmot… and enter Bastideum, Monpazier’s heritage centre. The garden is behind the building. (Note for photographers: the best view is from the window on the centre’s upper floor, see right). In truth, the garden is a re-creation but, in matters horticultural, authenticity can be more important than age. It was planned and planted in 2010 by the municipality with the help of students from the agricultural school of Monbazillac, working with Dordogne’s departmental centre for landscaping.

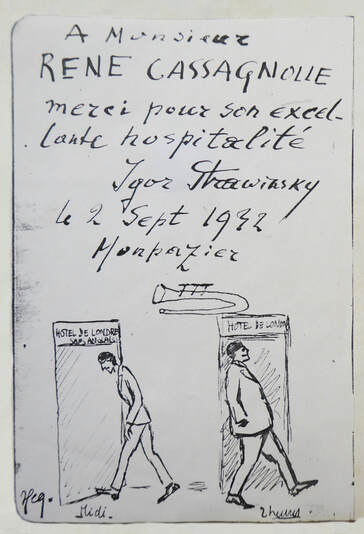

LAWRENCE OF MONPAZIER ?

Not as improbable as you might think…

During the summer of 1908, the 19-year-old T.E. Lawrence, then a student at Jesus College, Oxford, embarked on a solo cycling tour of French castles connected with Richard the Lionheart. The trip – to gather research for his thesis on medieval military architecture - lasted two months, covered nearly 4000 kilometres… and entailed as many punctures as castles.

After a visit to the Château de Bonaguil, the future ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ stayed overnight in Monpazier before moving north.

Unfortunately he doesn’t specify where he lodged. There are, though, two contenders: L’Hotel de Londres and L’Hotel de France. L’Hotel de Londres – a 19th century building opposite the north gates now occupied by the Bistrot-2 restaurant – was a favourite staging post for British travellers and had a reputation as a gourmet hot-spot.

Not as improbable as you might think…

During the summer of 1908, the 19-year-old T.E. Lawrence, then a student at Jesus College, Oxford, embarked on a solo cycling tour of French castles connected with Richard the Lionheart. The trip – to gather research for his thesis on medieval military architecture - lasted two months, covered nearly 4000 kilometres… and entailed as many punctures as castles.

After a visit to the Château de Bonaguil, the future ‘Lawrence of Arabia’ stayed overnight in Monpazier before moving north.

Unfortunately he doesn’t specify where he lodged. There are, though, two contenders: L’Hotel de Londres and L’Hotel de France. L’Hotel de Londres – a 19th century building opposite the north gates now occupied by the Bistrot-2 restaurant – was a favourite staging post for British travellers and had a reputation as a gourmet hot-spot.

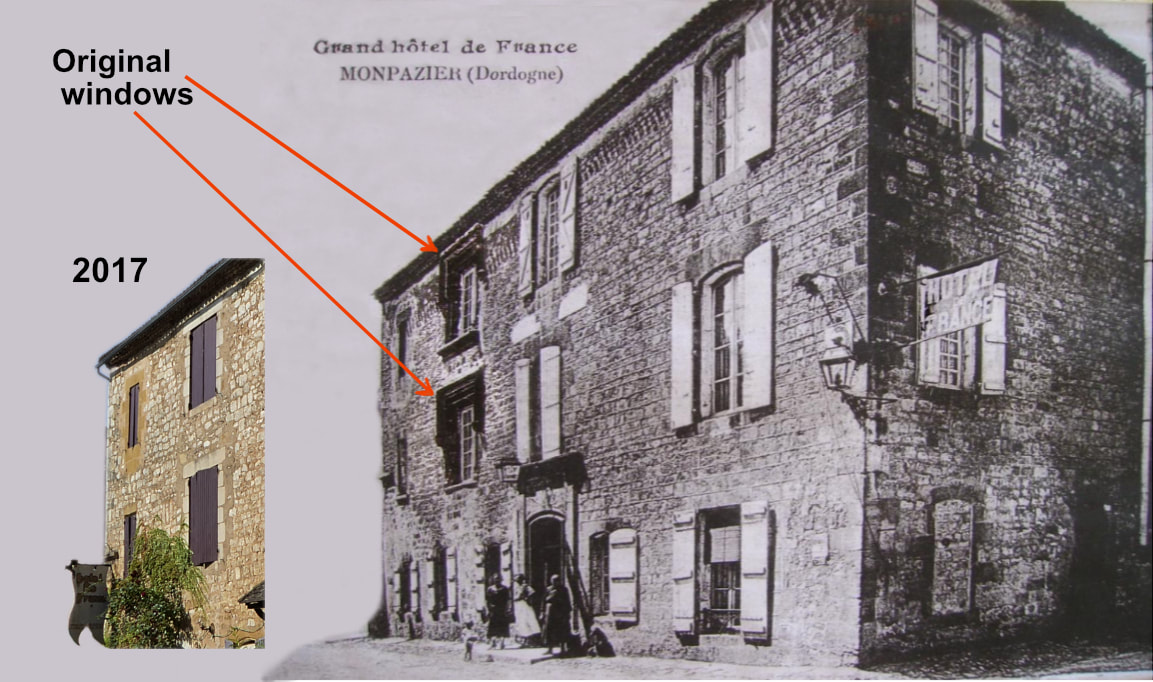

But the two-wheeling Lawrence was travelling on a student’s budget and in a letter to his mother he talks of staying in a huge room with 'a glorious Renaissance window' accessed by a handsome staircase. This would perfectly fit the Hotel de France (now Le Chevalier Bleu). The window disappeared in subsequent renovations, along with some fine sculptures - flogged off to Americans in the late 1920s.

The staircase, though, remains. See photo left.

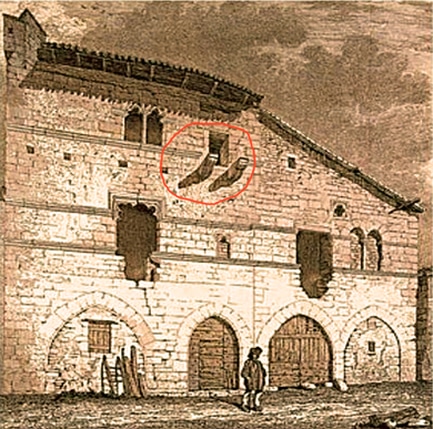

But which room did T.E. stay in? The window is a clue. Below is an old postcard of the Hotel de France taken in the early 1900s. Look closely and you can make out the projecting stone mullions of not one, but two windows in 'the Renaissance style' on the first and second floors. 'Glorious' indeed. Lawrence could have stayed in either.

The staircase, though, remains. See photo left.

But which room did T.E. stay in? The window is a clue. Below is an old postcard of the Hotel de France taken in the early 1900s. Look closely and you can make out the projecting stone mullions of not one, but two windows in 'the Renaissance style' on the first and second floors. 'Glorious' indeed. Lawrence could have stayed in either.

As for Monpazier, Lawrence describes it as ‘a little town fast going to ruin.’ Just as well his grasp of the past was better than that of the future. That said, could now - over a century later - be the time to lobby for a blue plaque? Artist's impression right - and below, a photo of the Hotel de France as it was in 2016 before closing, being renovated and, post pandemic, re-born as Le Chevalier Bleu.

Sources: Elisée Cérou, article in Cahiers du Groupe Archéologique de Monpazier 1987; Archives départementales de la Dordogne. Lawrence's letter to his mother, 16.08.08, published in 'The Home Letters of T.E.Lawrence and his Brothers', (Basil Blackwell, Oxford, 1954).

A full-length article on Lawrence's 1908 'Tour de France' appears in Edition no.11 of 'Secrets de Pays' magazine. The French version is available online at:

www.espritdepays.com/dordogne/histoire/lawrence-du-perigord

A full-length article on Lawrence's 1908 'Tour de France' appears in Edition no.11 of 'Secrets de Pays' magazine. The French version is available online at:

www.espritdepays.com/dordogne/histoire/lawrence-du-perigord

GONE WEST

The Hotel de France’s renaissance windows weren't the only items sold off to Americans back in the 1920s. The ornate entrance to a twelfth century chapel round the corner on the Rue Saint Pierre (see right) was also dismantled, crated up and sent west – though whether by the same buyer isn’t clear.

The Hotel de France’s renaissance windows weren't the only items sold off to Americans back in the 1920s. The ornate entrance to a twelfth century chapel round the corner on the Rue Saint Pierre (see right) was also dismantled, crated up and sent west – though whether by the same buyer isn’t clear.

Here's what the building looks like today - naked.

If anybody knows where the stonework is now, the current owner would be interested to hear from them...

Contact me (see top line) and I'll pass on the information.

If anybody knows where the stonework is now, the current owner would be interested to hear from them...

Contact me (see top line) and I'll pass on the information.

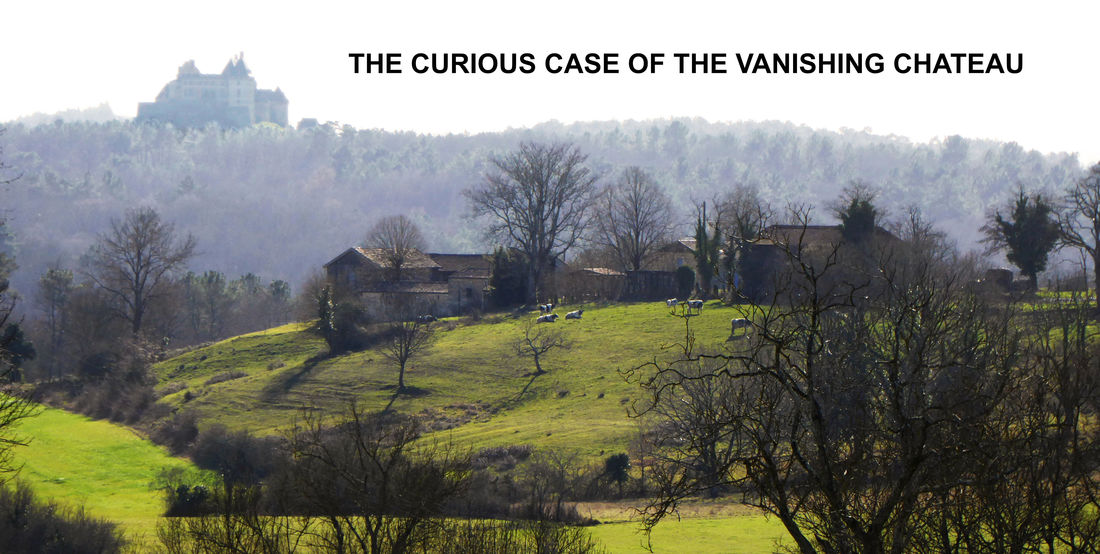

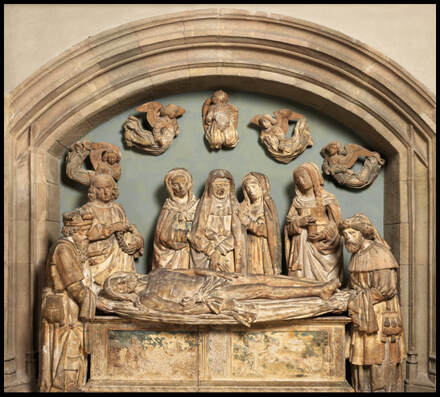

While on the subject of trans-Atlantic 'relocations'... the most famous - notorious? - example locally is that of two early 16th century works originally in the chapel of the nearby Château Biron: an Entombment of Christ and a Pietà. They were commissioned by members of the Gontaut family, lords of Biron, whose ancestor Pierre de Gontaut had been Edward 1st's 'business partner' in the founding of Monpazier two centuries earlier. They were acquired by the industrial magnate and global collector J.Pierpoint Morgan in the late 19th or early 20th century - and left in his will to the Metropolitan Museum, New York, where they can be seen today.

Entombment of Christ, c. 1515, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Entombment of Christ, c. 1515, Metropolitan Museum of Art

It’s tempting, with the benefit of 21st century hindsight, to describe the removal of the above works as ‘cultural plunder’ – on a par with Lord Elgin’s dodgy ‘purchase’ of the Acropolis sculptures in the early nineteenth century. But rather than asking how much the Americans paid for them, perhaps we should be asking how much the locals received. Both parties were complicit.

More to the point, why didn't the authorities stop it? Local architects were appointed to protect France’s historic monuments as long ago as 1897. But it wasn’t until 1946, just after WW2, that the body known as ‘Architectes des bâtiments de France’ was created with a duty not just to protect specific monuments but to supervise ‘the quality’ of buildings in the immediate vicinity. Since 1995, the ABF has come under the French Ministry of Culture – and today wields considerable power to protect the local patrimoine. In this case, nearly a century too late.

More to the point, why didn't the authorities stop it? Local architects were appointed to protect France’s historic monuments as long ago as 1897. But it wasn’t until 1946, just after WW2, that the body known as ‘Architectes des bâtiments de France’ was created with a duty not just to protect specific monuments but to supervise ‘the quality’ of buildings in the immediate vicinity. Since 1995, the ABF has come under the French Ministry of Culture – and today wields considerable power to protect the local patrimoine. In this case, nearly a century too late.

INTO THE WOODS... This is the view from the western flank of the village in early May. In medieval times, the forested areas that surround Monpazier were an asset to be exploited. Not just wood and nuts, as already mentioned, but also game - gibier - in the form of rabbits and wild fowls. There were boar and deer too, though you'd be wise to leave those to the 'recreational' hunters, the nobility. The earth beneath was rich in iron-ore - an essential raw material for the local blacksmiths, whose furnaces also required charcoal, made in the forests by the charbonniers from the wood of the trees. To misquote Julie Andrews, the hills would have been alive with the sound of humanity...

Sadly, I don't know his name but he and his minder are regular - and welcome - visitors to the village whenever there's a festival or 'animation'. Never mind his name, perhaps I should also check on 'his' sex before making assumptions.

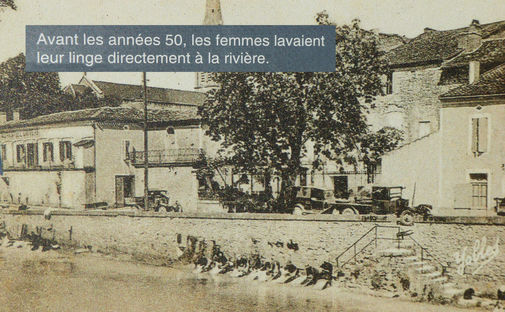

STEPPING OUT: The rural French, it’s fair to say, really don’t understand the concept of the pavement (aka ‘sidewalk’). You do find pavements, of a sort, in supposedly urban areas like Monpazier, but only in lethally fragmented form. Every few metres the pedestrian is confronted by an obstacle – a pot of flowers, a table and chairs - even, here in the Rue Saint Pierre, a pair of stone troughs and a flight of steps up to a garden on a higher level.

Generally the only way round is to step into the road and risk being side-swiped by the speeding white van of Monsieur Robinet, the plumber. The old adage holds true: there are two sorts of pedestrian - the quick and the dead.

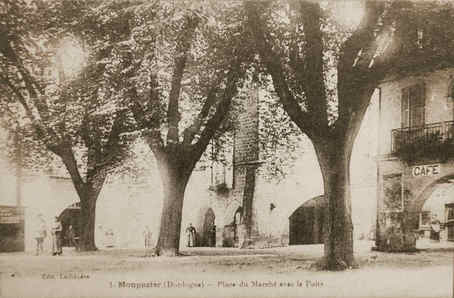

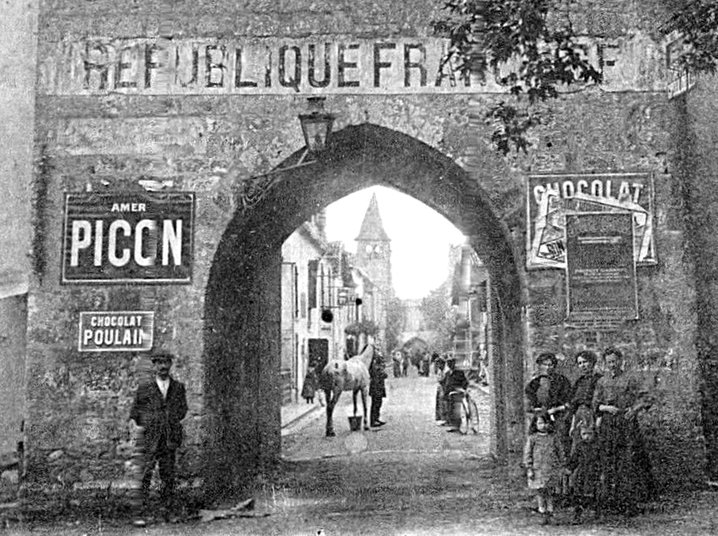

* It's probably no accident that the French for 'pavement' is 'trottoir' - literally a place for 'trotting'. So, think horses not humans. It must also be significant that all those old sepia postcards show people walking and standing in the middle of the road. Back then, there would have been no need for a dedicated pedestrian pavement because there were no motor vehicles - while the horses, presumably, kept to the 'trottoir'.

Generally the only way round is to step into the road and risk being side-swiped by the speeding white van of Monsieur Robinet, the plumber. The old adage holds true: there are two sorts of pedestrian - the quick and the dead.

* It's probably no accident that the French for 'pavement' is 'trottoir' - literally a place for 'trotting'. So, think horses not humans. It must also be significant that all those old sepia postcards show people walking and standing in the middle of the road. Back then, there would have been no need for a dedicated pedestrian pavement because there were no motor vehicles - while the horses, presumably, kept to the 'trottoir'.

LA PLACE DES CORNIÈRES – DE PANISSALS’ CUNNING PLAN

The man who laid out Monpazier's distinctive grid pattern was Bertrand de Panissals. Loyal to Edward 1st, he was responsible for other English bastides but Monpazier gave him the chance to work on a superb 'green-field' site: a high plateau measuring 400 by 220 metres overlooking the valley of the River Dropt, with level access from the north but falling away steeply on the other three sides. So, not just constructible but défendable. Monpazier would be de Panissals' masterpiece. It is thanks to his genius, his understanding of the way humans function, interact and move around, that Monpazier is such a perfect 'machine for living'. Nowhere is this better demonstrated than in the central Place des Cornières.

The man who laid out Monpazier's distinctive grid pattern was Bertrand de Panissals. Loyal to Edward 1st, he was responsible for other English bastides but Monpazier gave him the chance to work on a superb 'green-field' site: a high plateau measuring 400 by 220 metres overlooking the valley of the River Dropt, with level access from the north but falling away steeply on the other three sides. So, not just constructible but défendable. Monpazier would be de Panissals' masterpiece. It is thanks to his genius, his understanding of the way humans function, interact and move around, that Monpazier is such a perfect 'machine for living'. Nowhere is this better demonstrated than in the central Place des Cornières.

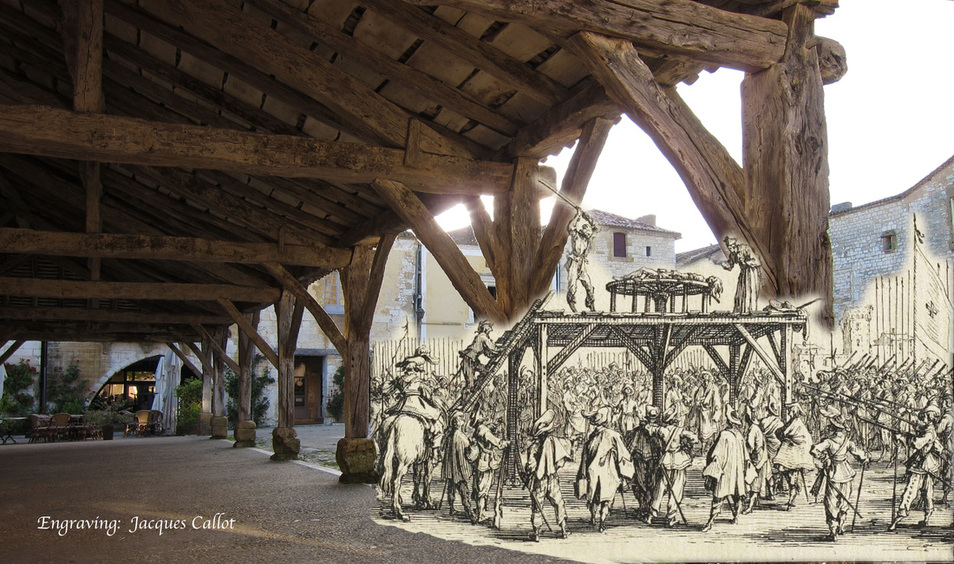

The square was – and still is – the beating heart of Monpazier. For seven centuries, it’s been the designated place for the weekly Thursday market, as well as fairs and other events. Its most obvious feature is its fringe of arcades, running around the perimeter – an early form of shopping mall which, along with the covered halle on the southern side, enables buyers and sellers to go about their business protected from the elements, whether blistering sun or driving rain.

Watercolour of La Place des Cornières: MD

Watercolour of La Place des Cornières: MD

More complicated – and for the planner a far greater challenge - is the way the square connects with the town’s main thoroughfares, north-south and east-west. And never more important than on market days when all roads lead to the square.

The logical layout – to be seen in countless other civic grid-plans around the world – is to make the square the intersection, so that the thoroughfares enter and exit at right-angles at the mid point of each side. Logical maybe but, if the square is full of people and possibly animals too, not very practical. The incoming traffic will be in constant conflict with the stalls, pens and any number of informal human groupings. The result will be an unintended 'quartering' of the area.

But Bertrand de Panissals had a cunning plan, My Lord (with apologies if you've never seen the BBC TV series ‘Blackadder’).

The logical layout – to be seen in countless other civic grid-plans around the world – is to make the square the intersection, so that the thoroughfares enter and exit at right-angles at the mid point of each side. Logical maybe but, if the square is full of people and possibly animals too, not very practical. The incoming traffic will be in constant conflict with the stalls, pens and any number of informal human groupings. The result will be an unintended 'quartering' of the area.

But Bertrand de Panissals had a cunning plan, My Lord (with apologies if you've never seen the BBC TV series ‘Blackadder’).

Instead of the main axes entering the square at the mid point of each side, de Panissals lined them up with the arcaded edges. On non-market days, the traffic – whether human, animal or vehicular (carts and wagons in his time) – is mostly 'through traffic' and, having no need to enter the central area, it maintains its direction of travel, unimpeded, beneath the arches* [orange lines below]. The square itself is effectively bypassed and so likewise unimpeded. But on market days, when much of that traffic does need to enter, access is diagonally, from the corners [the blue line]. It flows into the square like a river, rather than cutting in like a knife. It has access but not priority. In modern terms, it’s the difference between a roundabout and a cross-roads.

There is, incidentally, a 'strategic detail' here that was most likely a later refinement. The photo above shows the entrance from the rue Notre Dame into the north-east corner of the square. Note how the junction between the two buildings forms a high triangular arch. It's a pattern that is repeated in the diagonally opposite corner of the square. The reason? The theory is that this was to enable armed horsemen to enter and exit the square without having to dismount - or lower their lances. Very useful at times of civil unrest if it were necessary to clear the area. For proof that it worked, see photo right...

You have only to wander around the annual Flower Fair in May - or any market day during the tourist season - to see that de Panissals' plan works as well today as it did seven hundred years ago.

* It wasn't until 1987 that motor vehicles were stopped from driving through the arcades - and then only during the summer months. Hard to believe but only in December 1994 was a total year-round ban finally imposed.

* It wasn't until 1987 that motor vehicles were stopped from driving through the arcades - and then only during the summer months. Hard to believe but only in December 1994 was a total year-round ban finally imposed.

Time for 'une petite pause café' ?

Here the medieval warriors in clanking armour (if only in my imagination) would strut their manly stuff, their ornate helms under their arms. Fast forward seven centuries... and today's motorbike warriors unconsciously mirror the past, their 21st century helms neatly lined up while they sip their cafés crèmes.

The covered 'halle' on the southern side of the square - complete with its three different-sized metal bins for measuring grain and, no less important, calculating the taxes.

THE JUPITER JOINT

Back in the 1990s a Dutch friend showed me round his medieval chateau on the slopes of Penne d’Agenais, just over the departmental border in the Lot-et-Garonne. Up in the roof space, he asked: ‘Remind you of anything?’ When I responded, 'Looks like an upside-down boat’, he explained that boat-builders in Bordeaux would move inland to find work when times were tough. For them, building a roof was no more complicated than building a boat – only the other way up… or down. The overall shape aside, the big give-away, he said, was the jointing – the sort used mainly or exclusively by boat-builders. It’s a story I’ve heard several times since – and if you want to see one of the best examples of marine jointing in a roof, you have only to drive twenty minutes north-west of Monpazier...

Back in the 1990s a Dutch friend showed me round his medieval chateau on the slopes of Penne d’Agenais, just over the departmental border in the Lot-et-Garonne. Up in the roof space, he asked: ‘Remind you of anything?’ When I responded, 'Looks like an upside-down boat’, he explained that boat-builders in Bordeaux would move inland to find work when times were tough. For them, building a roof was no more complicated than building a boat – only the other way up… or down. The overall shape aside, the big give-away, he said, was the jointing – the sort used mainly or exclusively by boat-builders. It’s a story I’ve heard several times since – and if you want to see one of the best examples of marine jointing in a roof, you have only to drive twenty minutes north-west of Monpazier...

The hilltop town of Belvès boasts a fine 15th century market halle (see left). In 2016, after a fire destroyed part of one of the roof’s main beams, it was decided to replace the damaged part by grafting a new section on to what remained. As an hommage to the boat-builders of earlier centuries, wood-worker Vincent Papeix used one of the most famous, most complicated and most secure, of all marine joints – known in French as un trait de Jupiter; in English, a Jupiter joint. It's so called because in profile it looks like the lightning bolt which the Roman god hurled at his enemies (see close-up photo below).

The joint, which is tightened by banging in a pair of 'key wedges' from opposing sides, was often used by boat-builders when laying a keel – the backbone of a hull. Eight metres was generally reckoned to be the maximum length you could get out of an oak or chestnut tree. But keels often had to be longer – and, always, as straight as possible. Hence the need for secure jointing.

So impressive was the Belvès repair and so historically important its Jupiter joint that (with the agreement of the commune) a visiting artist, Brad Downey, coated the new wood in gold leaf so the work would stand out when viewed from below. The reaction of the heritage preservation authority, Les Batiments de France, is not known.

So impressive was the Belvès repair and so historically important its Jupiter joint that (with the agreement of the commune) a visiting artist, Brad Downey, coated the new wood in gold leaf so the work would stand out when viewed from below. The reaction of the heritage preservation authority, Les Batiments de France, is not known.

THE CURSE OF CRENELATION

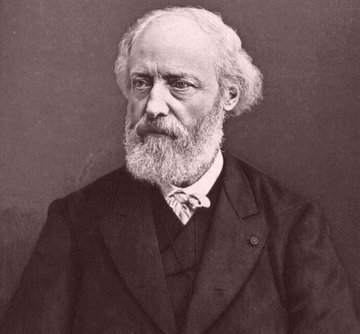

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879) was the nineteenth century guru of French architecture – a contemporary of John Ruskin in England with a comparable status and influence. And he had a particular attachment to Monpazier. Indeed, Monpazier has reason to be grateful for the interest he showed - and arguably even more grateful that he didn't show more...

Portrait: public domain

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814-1879) was the nineteenth century guru of French architecture – a contemporary of John Ruskin in England with a comparable status and influence. And he had a particular attachment to Monpazier. Indeed, Monpazier has reason to be grateful for the interest he showed - and arguably even more grateful that he didn't show more...

Portrait: public domain

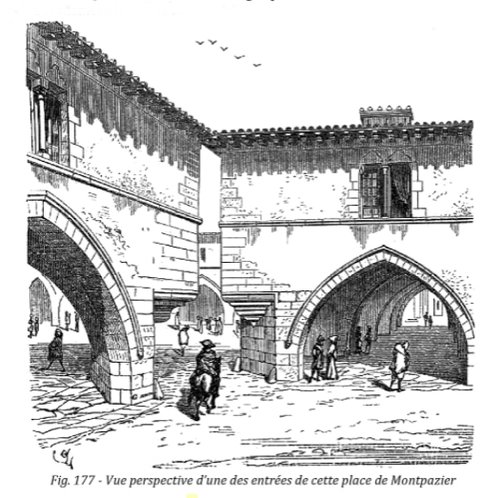

Like Ruskin, Viollet-le-Duc was an enthusiastic promoter of the architecture of the past, particularly the Gothic period, assiduously cataloguing buildings in words and drawings, and thereby recording their details for posterity. The work for which he is best remembered is his monumental Dictionnaire Raisonné de l'Architecture Française (all ten volumes from the 11th to 16th centuries). Monpazier gets more than a passing mention; it is held up as the perfect exemplar of the medieval bastide and a model of town planning of any age. He was particularly struck by, first, its egalitarian layout, how it had been designed according to the essential needs of its inhabitants and, second, by the ingenious design of the central square (see article above about Bertrand de Panissals). By focusing on Monpazier in this detailed way Viollet-le-Duc drew the attention of others – including, in the next century, Le Corbusier. The fact that the town has been accorded the highest level of protection, un grand site national, can be traced directly back, via Le Corbusier, to Eugène Viollet-le-Duc*.

But this was no library-bound academic; he was a trained architect who believed in applying his passions - by reconstructing buildings and whole towns which had suffered through wear, tear, neglect or conflict. ‘Re-imagining’ might be a better word and the man himself wouldn’t have demurred: 'To restore an edifice', he observed in the Dictionnaire Raisonné, 'is not to maintain it, repair or rebuild it, but to re-establish it in a complete state that may never have existed at a particular moment.'

But this was no library-bound academic; he was a trained architect who believed in applying his passions - by reconstructing buildings and whole towns which had suffered through wear, tear, neglect or conflict. ‘Re-imagining’ might be a better word and the man himself wouldn’t have demurred: 'To restore an edifice', he observed in the Dictionnaire Raisonné, 'is not to maintain it, repair or rebuild it, but to re-establish it in a complete state that may never have existed at a particular moment.'

Restoration has always been a controversial area and through our 21st century eyes Viollet-le-Duc’s interpretation borders on ‘Disneyfication’. It is to Viollet-le-Duc that we owe Carcassonne in the reconstructed form we see today, with its crenelated walls, fairy-tale towers and slate-covered conical caps… these in a part of the country where terracotta tiles were the traditional norm. He also worked on Paris’s Notre Dame, adding a taller, more ornate central spire (yes, the one destroyed in the fire of April 2019. Perhaps the Almighty also had doubts about Viollet-le-Duc's architectural taste.). Meanwhile across the Channel... the very notion of restoration was anathema to his English contemporary. ‘It is impossible', Ruskin declared, 'as impossible as to raise the dead, to restore anything that has ever been great or beautiful in architecture.’

But Viollet-le-Duc’s intentions were good; his restorations can be seen as un hommage to give the contemporary visitor a better idea and understanding of the past. And, as his supporters point out, without his intervention many of the structures he restored would never have survived in any form. Problems arise when deciding which particular slice of the past to restore. Whichever period is chosen will likely involve the removal – i.e. destruction – of everything that follows and the covering up – i.e. disappearance - of what has gone before. Yet such was Viollet-le-Duc’s eminence that his restorations were enthusiastically commissioned by the conservation authorities of the day.

But Viollet-le-Duc’s intentions were good; his restorations can be seen as un hommage to give the contemporary visitor a better idea and understanding of the past. And, as his supporters point out, without his intervention many of the structures he restored would never have survived in any form. Problems arise when deciding which particular slice of the past to restore. Whichever period is chosen will likely involve the removal – i.e. destruction – of everything that follows and the covering up – i.e. disappearance - of what has gone before. Yet such was Viollet-le-Duc’s eminence that his restorations were enthusiastically commissioned by the conservation authorities of the day.

Which is why we should be grateful that no-one ever suggested he ‘restore’ Monpazier – or today we might see a running perimeter of crenelated battlements, pointy towers at every corner and, for good measure, a full complement of gates with working draw-bridges.

Far better to have, and to appreciate, his finely crafted ‘impression’ of the town in its medieval prime…

* I am over-simplifying a little here. A decade before Viollet-le-Duc highlighted Monpazier, the Perigordian archaeologist and historian Félix de Verneilh had drawn public attention to the region's remarkable 'New Towns of the Middle Ages' - a fact which Viollet-le-Duc himself acknowledges.

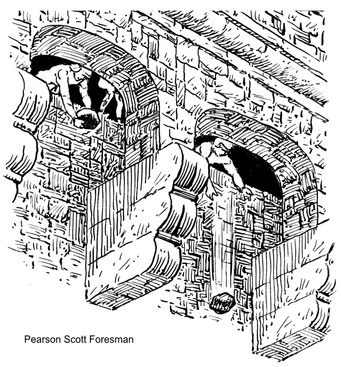

Drawing by Viollet-le-Duc from his Dictionnaire Raisonné de l'Architecture Française, showing how Monpazier's Place des Cornières is entered diagonally from the corners

Far better to have, and to appreciate, his finely crafted ‘impression’ of the town in its medieval prime…

* I am over-simplifying a little here. A decade before Viollet-le-Duc highlighted Monpazier, the Perigordian archaeologist and historian Félix de Verneilh had drawn public attention to the region's remarkable 'New Towns of the Middle Ages' - a fact which Viollet-le-Duc himself acknowledges.

Drawing by Viollet-le-Duc from his Dictionnaire Raisonné de l'Architecture Française, showing how Monpazier's Place des Cornières is entered diagonally from the corners

House martins are one of the delights or menaces (depending on your viewpoint) of Monpazier's central square, forever building their nests beneath its overhanging structures. For the local feline population they are a constant source of both interest and frustration. [Translation note: the French word for the bird is 'martinet', which is normally translated as a 'swift' - but to me they look like house martins. If there's an ornithologist out there, do get in touch...]